Myna birds

The myna (also known as Indian, Calcutta or house myna) is a medium-sized (25–26 centimetres head to tail) but heavily built bird with mainly brown plumage. It has a dark brown to black head with a bright yellow patch behind the eye, and a yellow bill, legs and feet. The wing patch, under-tail covets and tail tip are white. Mynas have a distinct strut or exaggerated hop when moving across the ground and can be in small to very large groups.

Voice

Varied repertoire: a coarse ‘karrarr’; a high trisyllable ‘weeo’; and a brisk ‘seeit’ in alarm.

Habitat

The common myna is a common inhabitant of urban areas, savannah, cleared agricultural lands, cultivated paddocks, plantations, canefields and roadside vegetation. Mynas are closely associated with human development, especially following initial introductions. Colonisation of surrounding agricultural areas and open woodlands can occur gradually, usually starting along roads or railways. The birds also have potential to colonise areas away from human settlement, such as coastal mangroves, flood plains and open forest, but are usually at lower density in these areas and avoid dense forests. In the Atherton Tablelands (Queensland) they now occupy all habitats except thick rainforest and populations are steadily expanding into agricultural areas of New South Wales and Victoria. Once the birds are established, dramatic increases in density are apparent. For example, in urban centres such as Canberra, Melbourne and the inner and surrounding areas of Sydney, mynas have proliferated. Preferred roosts are well-sheltered sites, particularly introduced trees and shrubs with dense foliage such as phoenix palms (Phoenix canariensis) or introduced pines where they are often observed with starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) and sparrows (Passer domesticus). Large communal roosts of up to 5000 can occur, but smaller roosts of 40–80 are more typical in Australia. Roosting behaviour involves loud calling at dawn and dusk and occasionally during the night.

Movements

This species is sedentary. No seasonal move ments and only localised dispersal patterns are evident in Australia. Local fluctuations in density are most likely due to high rates of juvenile mortality, which is typical of highly fecund species.

Density is therefore highest after the young leave the nest between December and March and lowest during the early stages of breeding in the following season. Intermittent juvenile or adult dispersal can occur along main roads and railways and may become more frequent as populations increase. Daily movements are also confined to small areas, often within three kilometres of a roost site. Preroosting flocks assemble in the late afternoons in cleared areas or perching on powerlines, antennae, bridges or other manufactured structures.

Mynas are highly adaptable omnivorous scavengers and feed on a variety of food scraps, fruits, vegetables, grains, seeds, flowers, nectar, young birds, eggs and invertebrates and their larvae. Unlike starlings, which commonly probe for invertebrates below the ground, these birds are ‘surface-feeders’. Their diet varies considerably with availability. Insects are regularly consumed in large quantities, particularly beetle (Coleoptera) and moth (Noctuidae) larvae, locusts, grasshoppers (Orthoptera) and flies (Diptera). They are frequent dwellers of rubbish dumps and often consume food scraps around buildings and food-processing plants and along roadsides. Mostly they forage in pairs or small family groups on the ground, but larger groups can feed in trees and shrubs for fruit and seeds. Mynas rarely feed far from roosting or nesting sites and in some urban areas they will restrict foraging to within 100 metres of the roost.

Breeding

Mynas are hole-nesting species. They have similar breeding habits to starlings but are more dominant. Pairs mate for life and vigorously defend territories and nest sites during the breeding season which extends from August to March.

Untidy nests of sticks, leaves, paper and other items are prepared in tree hollows, in the tops of palm trees, or in walls and ceilings of buildings. Two, or sometimes three, broods are raised per season, with 3–6 young per brood. Eggs are similar to those of starlings but marginally larger (31 × 22 millimetres) and a brighter blue.

Damage

Mynas can cause considerable damage to ripening fruit, particularly grapes, but also figs, apples, pears, strawberries, blueberries, guava, mangoes and breadfruit. Cereal crops such as maize, wheat and rice are susceptible where they occur near urban areas. Roosting and nesting commensal with humans create aesthetic and health concerns. Mynas are known to carry avian malaria and exotic parasites such as the Ornithonyssus bursia mite which can cause dermatitis in humans. The myna can help spread agricultural weeds: for example, it spreads the seeds of Lantana camara which has been classed as a Weed of National Significance because of its invasiveness. Mynas are regularly observed to usurp nests and hollows, kill the young and destroy the eggs of native bird species including seabirds and parrots (see list below) and kill small mammals although the extent to which these actions reduce native populations remains unquantified.

| Regent parrot1,4 | Polytelis anthopeplus |

| Coxen’s double- eyed fig parrot1,3 | Cyclopsitta diophthalma coxeni |

| Turquoise parrot1,3 | Neophema pulchella |

| Glossy black cockatoo1,3 | Calyptorhynchus lathami |

| Little tern2,3 | Sterna albifrons |

| Hooded plover2,3 | Thinornis rubricollis |

| Flesh-footed shearwater2,3 | Puffinus carneipes |

| White tern2,3 | Gygis alba |

| Sooty tern2,3 | Sterna fuscata |

- Competition for nest hollows.

- Potential predation of eggs or direct attacks.

- Occurs within the current distribution of the myna.

- Occurs within the potential distribution (Martin 1996) of the myna.

Protection status

Unprotected; introduced species.

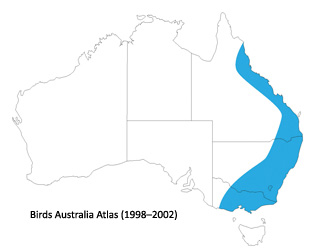

Distribution map

Other Publications

Sources and further reading

- Tracey, J., Bomford, M., Hart, Q., Saunders, G. and Sinclair, R. (2007) Managing Bird Damage to Fruit and Other Horticultural Crops. Bureau of Rural Sciences, Canberra.

- Byrd, G.V. (1979) Common myna predation on wedge-tailed shearwater eggs. Elepaio 39: 69–70.

- Counsilman, J.J. (1974) Breeding biology of the Indian myna in city and aviary. Notornis 21: 318–333.

- Counsilman, J.J. (1974) Waking and roosting behaviour of the Indian myna. Emu 74: 135–148.

- Feare, C. and Craig, A. (1999) Starlings and Mynas. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

- Grant, G.S. (1982) Common mynas attack black noddies and white terns on Midway Atoll. Elepaio 42: 97–98.

- Hermes, N. (1986) A census of the common mynah Acridotheres tristis along an axis of dispersal. Corella 10: 55–57.

- Hone, J. (1978) Introduction and spread of the common myna in New South Wales. Emu 78: 227–230.

- Martin, W.K. (1996) The current and potential distrubution of the common myna (Acridotheres tristis) in Australia. Emu 96: 166—173.

- Pell, A.S. and Tidemann, C.R. (1997) The impact of two exotic hollow-nesting birds on two native parrots in savannah and woodland in eastern Australia. Biological Conservation 79: 145–153.

- Pimentel, D., Lach, L., Zuniga, R. and Morrison, D. (2000) Environmental and economic costs of nonindigenous species in the United States. BioScience 50: 53–65.

- Wood K.A. (1995) Roost abundance and density of the common myna and common starling at Wollongong New South Wales. Australian Bird Watcher 16: 58–67.