Wetland habitats

Merrorie Creek wetlands. Photo: Dayle Green

A wetland isn’t necessarily always wet!

However, a wetland needs to be wet long enough to support the plants and animals that live in it for at least part of their life cycle.

Wetlands are depressions that are inundated permanently or temporarily with water that is usually shallow, slow moving or stationary The water in wetlands can be fresh, brackish, or saline. About 6% (45,000 sq km) of NSW is wetlands.

The term “wetland” includes a wide range of habitats. In freshwater are they include lakes, rivers, swamps, bogs, boggy areas in paddocks, floodplain meadows, billabongs and marshes. In coastal areas, they include upland lakes, estuaries, saltmarshes, mangrove forests, coastal swamps, lakes and lagoons. NSW DPI is actively involved in protecting and rehabilitating wetlands and working with landholders to conserve them on their properties.

Why are wetlands important to our fish?

NSW wetlands are estimated to support 52 fish species in the following ways:

- providing feeding and spawning for many species of freshwater and saltwater fish,

- providing nursery areas for juvenile fish,

- permanent waterholes become essential refuges for freshwater fish during dry times,

- acting as natural flood regulators,

- absorbing, recycling and releasing nutrients,

- triggering biological activity after inundation.

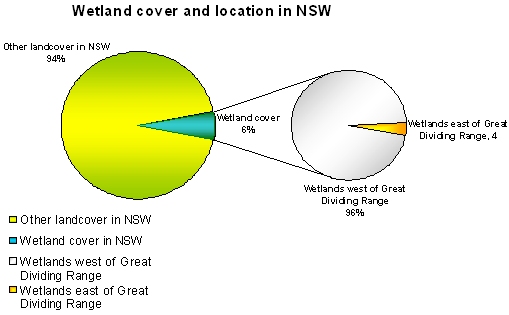

Wetlands in NSW

Wetlands cover nearly 6% of the land area of NSW. The distribution of wetlands is illustrated on the map below. What is clear from the map is that there is a greater area of wetlands in inland areas (that is, west of the Great Dividing Range) than in coastal areas,

Distribution of wetlands in NSW1

In fact, 96% of the land area identified as wetlands occurs west of the Great Dividing Range.

Many wetlands in NSW are adapted to dry out periodically. Many wetlands dry out each year (ephemeral) and some dry out for up to 6-9 years at a time.

This wetting and drying is critical for nutrient cycling. During the drying phase, exposed aquatic vegetation and other matter begins to dry out and decompose. Worms, insects, bacteria and other organisms break down the matter and work it into the soil profile, which helps to determine the type and productivity of the soils.

When water returns to the wetland, it comes to life and a sudden burst of nutrients becomes available for plants and fish. Plants start to sprout, insects, waterbirds, frogs, fish and mammals breed, hatch or arrive in their thousands. The result is a highly diverse and productive aquatic habitat.

Reference

- Kingsford, R.T., Brandis, K., Thomas, R., Crighton, P., Knowles, E. and Gale, E. (2003), The Distributionof Wetlands in New South Wales, New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Services, Sydney.