Estuarine habitats

Estuarine fish habitats occur where fresh water from rivers and streams mixes with the salty ocean water. This brackish water environment supports a variety of fish habitats, including:

These environments provide important feeding, spawning and nursery sites for many aquatic animals. There are animals, such as crabs and some mosquitoes, that rely on estuarine water to complete their life cycles and others, such as migratory shore birds, visit estuaries to feed and rest.

Did you know...

70% of coastal fish species in south-eastern Australia need to move through estuaries to complete their life cycle.1

Many fish species spend all or part of their life in estuaries and as a result estuaries support diverse and productive commercial and recreational fisheries and the oyster industry. These are important contributors to the local economies of many regional towns.

Estuaries in NSW

There are approximately 154 large and medium-sized estuaries and embayments along the NSW coast. Most of these are under intense urban development pressure with approximately 80% of the State’s population living near an estuary. Some 60% of the State’s estuaries are intermittently closed and open lakes and lagoons which are sensitive to what happens not only in the estuary but also throughout the lake's catchment.

A series of maps of the State's estuarine habitats are now available. Thse maps show the current distribution of core elements of estuarine habitat, such as saltmarsh, seagrass and mangrove.

Saltmarsh

View a map showing the saltmarsh in your estuary.

What is a saltmarsh?

A saltmarsh is a community of plants and low shrubs that can tolerate high soil salinity and occasional inundation from salt water. They usually have areas with vegetation interspersed with bare areas (salt pans). Saltmarshes occur at the upper levels of the intertidal zone, often behind mangroves, and, while they're not subject to daily tidal inundation, they're flooded by larger tides and semi-permanent pools of brackish water.2

Saltmarsh plants

Saltmarshes are characterised by plant species, such as Sarcocornia quinqueflora (samphire), Sporobolus virginicus (saltwater couch) and Juncus species (rushes).

Why are saltmarshes important?

41 fish species are known to use saltmarsh areas, including yellowfin bream, sand whiting and various mullets.2

Saltmarsh is important to fish as it provides sources of food, habitat and shelter when inundated at high tide. Saltmarshes play an important role as a juvenile habitat for species such as bream and mullet. Crabs are common in saltmarsh communities, and are a significant food source for bream and other fish species. Some species, such as common galaxias (Galaxias maculatus), deposit their eggs in saltmarsh vegetation. Saltmarshes also act as a buffer and filtration system for sediments and nutrients.

Where are saltmarshes found in NSW?

Saltmarshes can be found in estuaries along the whole NSW coastline, with the larger areas occurring in the Manning bioregion (between Nambucca Heads and Stockton). Saltmarsh is found in many estuaries of NSW and covers a total area of approximately 59km4. The distribution of major areas of saltmarsh in NSW is shown in the table below.5

Bioregion | Number of estuaries | Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|

Tweed / Morton (north of Nambucca Heads) | 28 | 5.5 |

Manning (Nambucca Heads to Stockton) | 18 | 36.5 |

Hawkesbury (Stockton to Shellharbour) | 17 | 4.9 |

Batemans (Shellharbour to Tathra) | 57 | 10.7 |

Twofold (south of Tathra) | 13 | 1.5 |

Total NSW | 133 | 59.1 |

Status of saltmarsh in NSW

Within NSW, saltmarsh area is contracting, with losses of between 12% and 97%. Part of this is due to the expansion of mangroves.4 Mangroves move landward because of changes in rainfall patterns, sea level rise, tidal changes due to harbour dredging, sedimentation and changes to the catchment.6 In many areas the extent and health of saltmarsh communities has rapidly declined due to pressure from rural and urban development.

Coastal saltmarshes have been listed as an Endangered Ecological Community under the Threatened Species Conservation Act, administered by the Department of Environment and Climate Change. For more information visit Saltmarsh as an Endangered Ecological Community (www.threatenedspecies.environment.nsw.gov.au).

Mangroves

- Primefact: Mangroves

- View a map showing the mangroves in your estuary.

Mangroves grow along the shores of many NSW estuaries, and in some places form extensive forests. Of the five species of mangrove that occur in NSW, Avicennia marina (Grey Mangrove) and Aegiceras corniculatum (River Mangrove) are the two most common.

Mangrove-lined creeks are important habitats for fish, crabs, birds and other animals. Mangrove trees provide large amounts of organic matter, which is eaten by many small aquatic animals. In turn, these animals provide food for larger fish and other animals. Mangroves also help maintain water quality by filtering silt from runoff and recycling nutrients.

Mangroves also play a vital role in protecting foreshores from storm surges, cyclones, tsunamis and wind and wave conditions.

In some areas, there has been a large decline of mangroves due to clearing or reclamation and changes in water flow from waterfront developments. In other areas, mangrove communities are expanding due to the build up of sediments from catchment clearing, development and stormwater run-off.

Mangroves are protected in NSW and a permit of required from NSW DPI to undertake works or activities that may harm them.

- Permit: Permit application form for harm to marine vegetation

Seagrass

- Primefact: Seagrasses

- View a map showing the seagrass in your estuary.

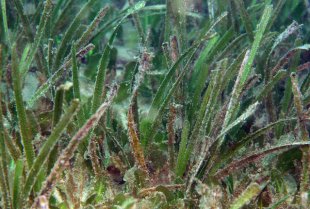

Seagrasses occur in the intertidal and subtidal zones of estuaries. The total area of seagrass in NSW is approximately 154km2.4 The area of seagrass beds can be highly variable seasonally as seagrasses die back during the cooler months and re-establish in warmer months of the year.

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants that can live underwater.7 The most common species in NSW are Zostera capricorni (eelgrass) and Halophila spp (paddleweed). Posidonia australis (strapweed) is limited to the more marine-dominated estuaries of central and southern NSW.

Seagrasses are particularly valuable as nursery, feeding and shelter areas for many aquatic animals, including commercially and recreationally important fish, crabs and prawns. Seagrass meadows are renowned world wide as rich and productive nursery areas for juveniles of economically important species. Research in the Mediterranean has found that 400 square metres of seagrass can support up to 2000 tonnes of fish a year.8 Along the NSW coast, luderick, bream and snapper are found as juveniles within seagrasses.9

Did you know...

Many major estuaries in NSW have lost as much as 85% of their seagrass beds in the past 30-40 years.10

Like other estuarine vegetation, seagrasses contribute organic matter to the food chain, and remove nutrients from the water. Seagrasses are particularly valuable because they grow quickly and produce a large amount of organic material. The primary productivity of several species of seagrass has been measured, and in general it has been estimated that each hectare of seagrass bed can generate up to 20 tonnes of organic leaf material each year.8

Seagrasses also baffle water currents, causing them to drop their sediment loads, thus maintaining water quality.

Seagrasses are, however, a fragile habitat. Some species can recolonise areas but other do not and are particularly sensitive to impacts. Posidonia species do not recolonise areas after removal.

Seagrasses are protected in NSW and a permit is required from NSW DPI to undertake works or activities that may harm them.

- Fish Habitat Protection Plan: Seagrass

- Permit application form for harm to marine vegetation

Macroalgae

Macroalgae are members of the huge group of aquatic plants know as algae. The algae are primitive photosynthetic plants that include single celled ‘phytoplankton’and the multi-celled macroalgae, or seaweeds. Macroalgae should not be confused with seagrass.

Sand and mudflats

Habitats with no vegetation, such as shallow mud flats, sand flats and deeper soft substrate areas, are the most common habitats in estuaries. They support a very diverse benthic (bottom-dwelling) community, including worms, crabs and yabbies. This, in turn, provides food for many fish species such as flathead and whiting.

Coastal lagoons

Coastal lagoons are often characterised by entrances to the sea which intermittently open and close. The characteristics of this habitat are a function of how often the ocean entrance opens and closes, the width and orientation of the mouth, the size and character of the freshwater catchment upstream, and the size and shape of the lagoon itself.

Intermittently opening and closing coastal lagoons (ICOLLs) are a special type of estuary with unique features. (More about ICOLLs and their management.) They don't generally support large mangrove or seagrass communities but can have an abundance of the macrophyte Ruppia species (sea tassel) and fringing wetlands with Casuarina species, Melaleuca species, and brackish rushes and reeds.

Mullet, bream and prawns can grow to large sizes in closed lagoons. This can enhance their chances of surviving and reproducing when the lagoon subsequently opens and they make their way into coastal waters.

The timing of the lagoon opening can favour different species at different times. A spring/summer opening favours tarwhine, snapper, sand whiting, luderick, leatherjackets and prawns, while an autumn or winter opening favours yellowfin bream, dusky flathead and flat tail mullet.10

References

- Copeland C., & Pollard D. (1996) The value of NSW commercial estuarine fisheries, Internal Report - NSW Fisheries, Cronulla.

- Morrisey, D. (1995) Saltmarshes, in A.J.Underwood and M.G. Chapman (eds), Coastal Marine Ecology of Temperate Australia, Chapter 13, UNSW Press, Sydney; and Adam, P. (1990) Saltmarsh Ecology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Thomas, B.E. and Connolly, R.M (2001) Fish use of subtropical saltmarshes in Queensland, Australia: relationships with vegetation, water depth and distance into the saltmarsh, Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser, 209:275-288.

- West, R.J., Thorogood, C., Walford, T. and Williams, R.J. (1985). An estuarine inventory for New South Wales, Australia. Fisheries Bulletin 2, Department of Agriculture, NSW, Australia.

- Wilton, K.M. (2002) Coastal wetland dynamics in selected New South Wales estuaries, Proceedings of the Australia’s National Coastal Conference, Tweed Heads, 4-8 November 2002, pp 511-514.

- Saintilan, N. and Williams, R.J. (1999) Mangrove transgression into saltmarsh in south-east Australia, Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters, 8: 117-124.

- Seagrass Watch (2007)

- Lloyd, D. (1996) Seagrass: A lawn too important to mow, Sea Notes, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority.

- Butler, A. and Jernikoff, P. (1999) Seagrass in Australia: A strategic review and development of an R&D plan, CSIRO, Canberra.

- NSW Fisheries (1999) Fish Habitat Protection Plan No 2: Seagrasses, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Cronulla.