Feral pigs

- Feral pigs are very adaptable and can thrive in most environments.

- They have significant impacts on agriculture production and the environment.

- Feral pigs are also a host and vector for numerous endemic and exotic diseases and parasites that affect both people and livestock.

Feral pigs occupy a wide range of habitat types in Australia (Photos Andrew Bengsen and Troy Crittle).

Description

Pigs arrived in Australia with the first fleet and were widespread across NSW by the 1880s.

Although feral pigs are descendants of various breeds of domestic pigs, they:

- are smaller than domestic pigs

- have more developed shoulders and necks, smaller hindquarters, and narrower backs

- have longer larger snouts and tusks

- have hair that is coarser, sparser, and longer

- males sometimes have a crest or mane of bristles extending down the middle of their back, which is longer on the neck and shorter near the tail and may stand up when agitated

- usually have straight tails with a bushy tip.

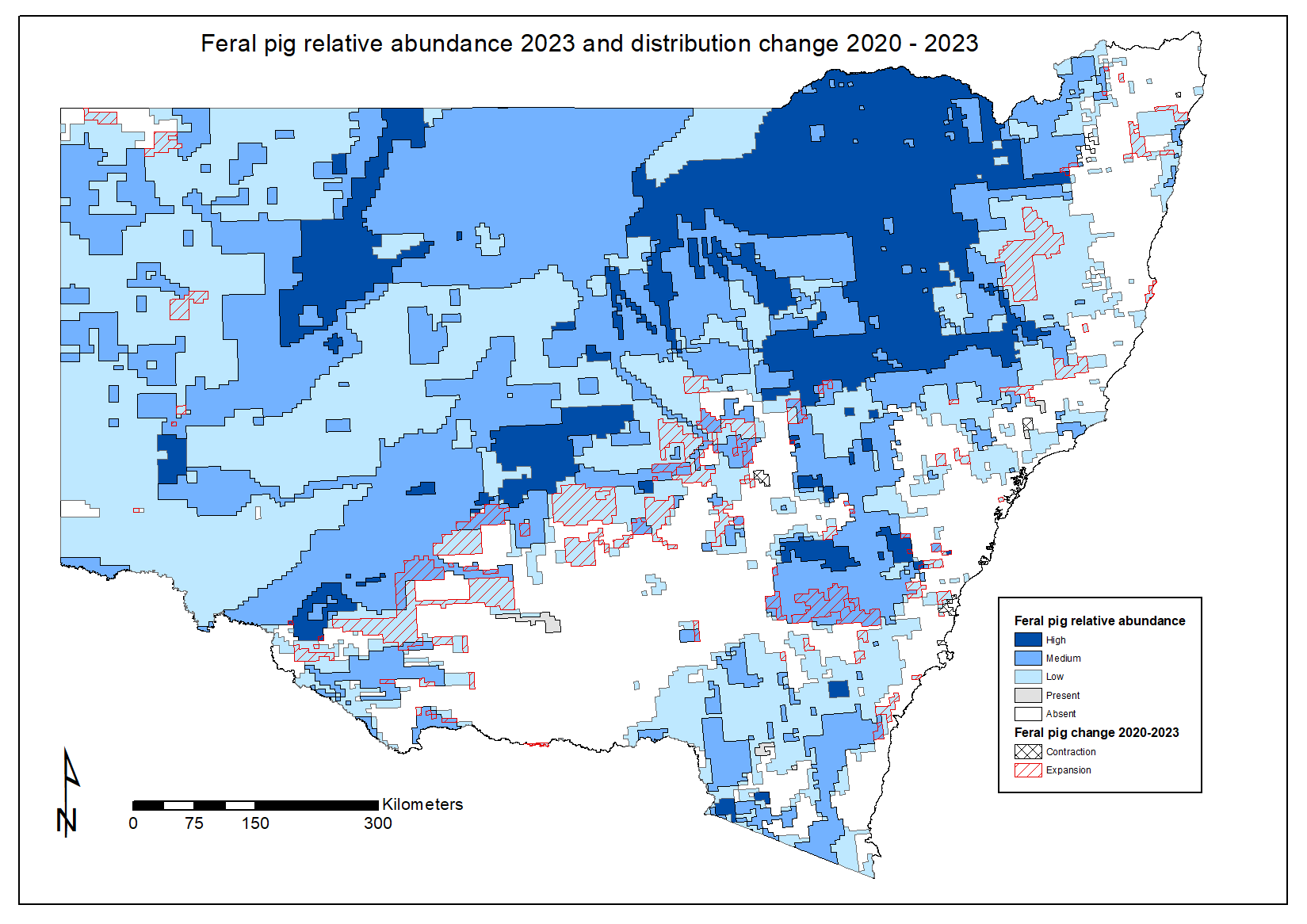

Distribution

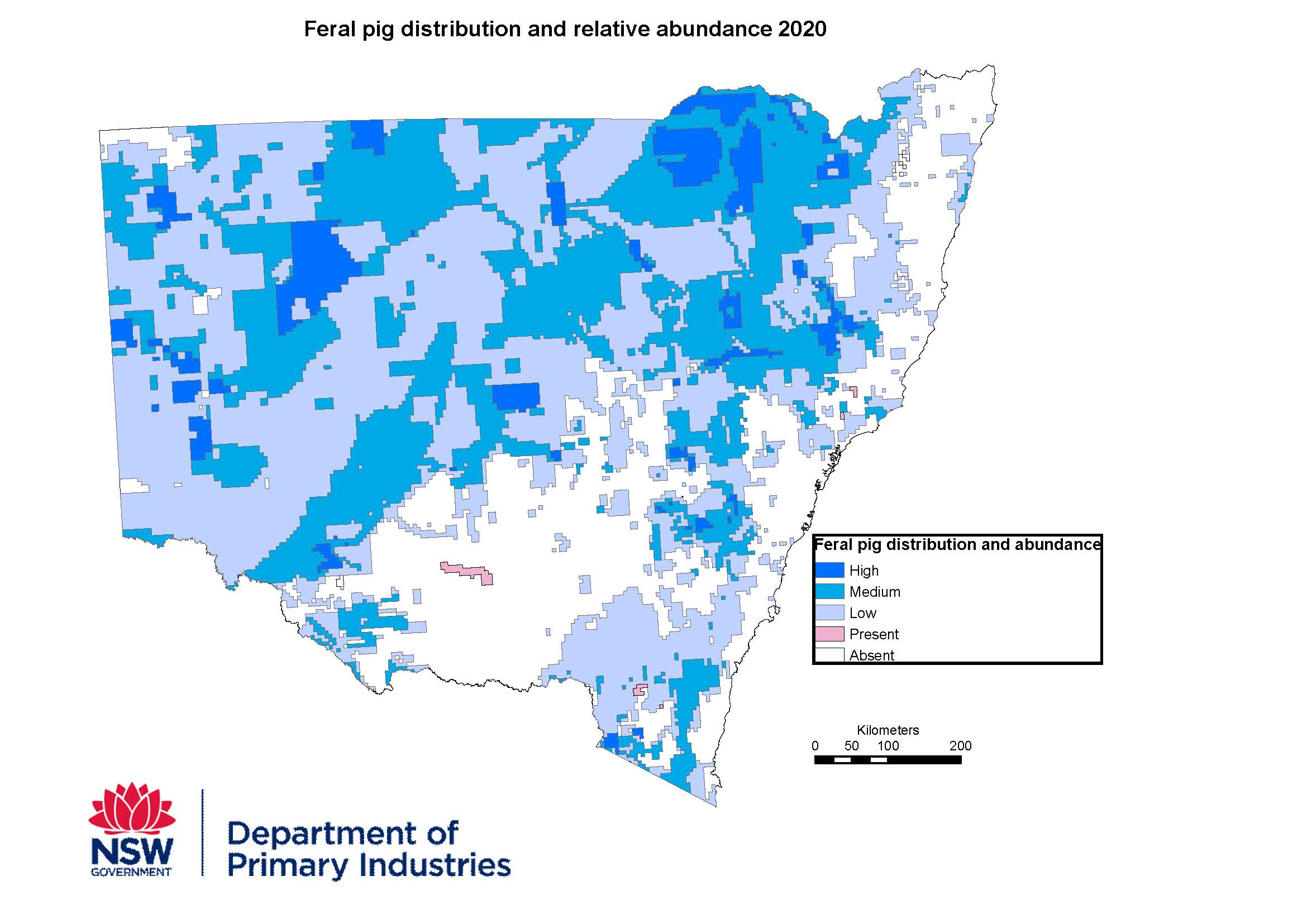

In NSW feral pigs are found in most regions west of the Great Dividing Range including the tablelands. High densities of feral pigs are found in western NSW floodplains and ephemeral wetlands as well as the northern slopes and plains.

Diet

Feral pigs are omnivores and have a monogastric digestive system. They will eat succulent green vegetation, meat, fruit, grain, bulbs and corms, and fungi. They can be fussy eaters and will often target specific food sources when they are available.

Ruminant animals, such as cattle, sheep, deer, and goats are more efficient than feral pigs at utilising grasses and other dry vegetation.

Reproduction

Feral pig breeding is flexible and greatly influenced by the amount and quality of feed available. Sows need a consistent high-protein food source to successfully breed and rear their offspring.

The feral pig:

- can breed throughout the year

- usually have litters of 4–10 piglets

- reach sexual maturity: for females, when they reach 25–30 kg in weight, between 7 and 12 months of age; and for males, at around 18 months of age.

When abundant high-quality feed is available, it:

- reduces the age when females start breeding

- reduces the time between breeding events

- increases litter size and survival rates of young.

When conditions are poor, pigs reduce breeding activity, conserving energy for survival instead of breeding.

When conditions are good feral pig populations can increase by up to 86% in one year.

Social structure

Feral pigs usually form groups where:

- sows and piglets generally remain together

- immature females and males form juvenile groups

- mature males tend to become more solitary only joining other groups to mate or share a common food source.

Group size depends on the seasonal conditions and habitat:

- in forested areas group size rarely exceeds 12

- in open country up to 40–50 feral pigs may form a group

- during dry times, when food and water is scarce, large groups of 100 or more may gather close to a water source.

Home range and movement

Feral pigs are mostly inactive, and they generally do not make regular long-distance movement from one habitat to another.

They need regular access to water and shelter as they cannot reduce their body temperature easily. This is especially important when conditions are hot.

The home range size is:

- influenced by the habitat and abundance of food sources

- size of individual animals and population density

- sex: adult males have a larger home range then females.

Feral pigs will often restrict activity to the cooler parts of the day. When temperatures get hot, days may be spent in one area and nights spent feeding in another nearby area.

Very hot conditions may greatly restrict movement resulting in:

- less feeding

- reduced mating opportunities

- less visibility in the landscape to casual observers.

Life span and mortality

Few feral pigs survive longer than five years. Mortality can vary depending on the habitat and seasonal conditions. Starvation effects feral pigs of all ages. Malnutrition can make feral pigs more susceptible to parasites and diseases.

Most piglets born will never reach one year of age. They can die due to:

- poor weather conditions

- accidental suffocation by sows

- separation from the sow

- malnutrition and starvation, sows can stop lactating if protein levels in their feed sources is not adequate

- predation.

Impacts

Feral pigs significantly impact agricultural production and the environment.

In agricultural production areas they:

- prey on newborn lambs and goats

- feed on and destroy or trample grain, sugarcane, fruit, and vegetable crops

- damage fences

- foul water sources like dams, and waterholes by defecating and wallowing in them

- damage pastures by uprooting the ground

- compete with livestock for pasture resources.

Environmental impacts include:

- degradation of natural areas by rooting up soils, native grasses, and forest litter

- eating a range of native animals or their eggs, including frogs, lizards, turtles, and ground nesting birds

- fouling water sources by trampling, wallowing and defecation in the water

- competing with other animals for food and water resources.

Social impacts include human disease spread, damage-related stress and damage to visual amenity (e.g. rooting up the ground in national parks).

Feral pig damage around a freshwater lagoon (Photo Jim Mitchell)

Disease spread

Feral pigs are hosts and vectors of spread for parasites and diseases which can affect other animals and people. Including:

- leptospirosis

- porcine brucellosis

- melioidosis

- tuberculosis

- sparganosis

- porcine parvovirus

- Murray Valley encephalitis and other arboviruses.

Feral pigs are susceptible to (or host and/or vector) several exotic diseases that may enter or are already present in Australia including:

- African swine fever

- foot and mouth disease

- swine vesicular disease

- Japanese encephalitis.

Publication

Feral pig management

- Control is most effective if applied when environmental conditions cause resource stress, such as when there is lack of food, water, or shelter for feral pigs.

- Large ongoing coordinated, broadscale, and integrated management programs provide the best means of managing feral pig populations over time.

- Generally, at least 70% of a feral pig population should be removed annually to keep numbers low and to prevent a rapid increase in feral pig numbers.

- Baiting and aerial shooting are the best control options to manage large populations of feral pigs. These techniques can be supported by trapping and ground shooting.

Control options

Baiting

Effective free feeding prior to baiting is essential to enable successful control.

Sodium fluoroacetate (1080)

Baiting feral pigs with 1080 is a cost efficient and effective way to control feral pigs and is particularly useful for reducing large populations.

1080 is a restricted chemical product. Private landholders can access 1080 bait products from a Local Land Services Authorised Control Officer.

Sodium nitrite (Hoggone®)

Hoggone® meSN is a commercially produced feral pig bait containing micro- encapsulated sodium nitrite as its active ingredient. Hoggone® is a Schedule 6 poison and is available through rural retailers in NSW. It is supplied as a peanut-based paste in a foil tray and must be used in conjunction with a pig-specific feeder.

Shooting

Aerial shooting

Aerial shooting can be expensive over a short period of time; however, due to the rapid population reduction it can achieve, it can often be a very financially and temporally efficient control method.

Aerial shooting is most effective in reducing feral pig populations following baiting programs (where accessible) and when feral pig densities are low enough (through seasonal conditions or baiting) that 1000 hectares can be covered in 2-3 hours of aircraft time. To further reduce populations and prevent regrowth of feral pig populations, follow-up aerial shooting programs are recommended within four months.

Aerial shooting can be a valuable tool for controlling feral pigs in tall standing crops and when feed sources are plentiful and therefore baiting is less effective.

Like most control methods, it is important to have coordination and cooperation across land tenure boundaries to increase effectiveness.

In NSW, aerial shooting is undertaken by both private contractors (who hold necessary CASA and firearms endorsements) and the NSW Government. NSW Government shooters are a part of the Feral Animal Aerial Shooting Team (FAAST) which is made up of National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and LLS staff. FAAST shooting is carried out under strict controls and procedures.

Ground shooting

Ground shooting and recreational hunting is a less effective for feral pig control, especially in areas of high feral pig populations.

Shooting feral pigs from the ground is a method normally used opportunistically to follow up and maintain low numbers after a primary control program such as baiting and aerial shooting has occurred.

Ground shooting is often conducted using dogs to locate feral pigs. Hunters must ensure both the dogs and the pigs are treated in a humane manner.

Ground shooting should not be conducted prior to, or during, any other program of control, as it disrupts normal feral pig activity and may cause feral pigs to break into smaller groups and move to other areas.

Trapping

Trapping of feral pigs is an effective technique to use:

- as a follow-up after an initial knockdown of a population using baiting or aerial shooting

- as an ongoing maintenance technique to prevent numbers from building back up

- where baiting cannot be carried due to risk to non-target animals or other legislative restrictions.

Trapping is flexible, as most traps can be easily moved to where pig activity is current. Such as:

- at watering points

- where pigs are moving regularly, e.g., under a hole in a fence, near a water source, into a crop or other feeding area.

As with baiting to be effective traps must use free feeding in the trap until all the pigs in the area are entering the trap. This means that the door mechanism needs to be disarmed and pigs are free to enter and exit the trap.

Some patience is required as wary pigs or new additions to a group may take 10-14 days to enter the trap.

Traps should always be sited in a location where they can be partially shaded because of pigs’ poor ability to dissipate body heat.

Fencing

Fencing is sometimes used to protect valuable enterprises in a small area. Effective pig proof fences have been designed but need to be thoroughly maintained to sustain their effectiveness.

Feral pig relative abundance 2023 and distribution change 2020 -2023

Distribution map 2009

Distribution map 2016

Feral pig distribution and abundance 2020

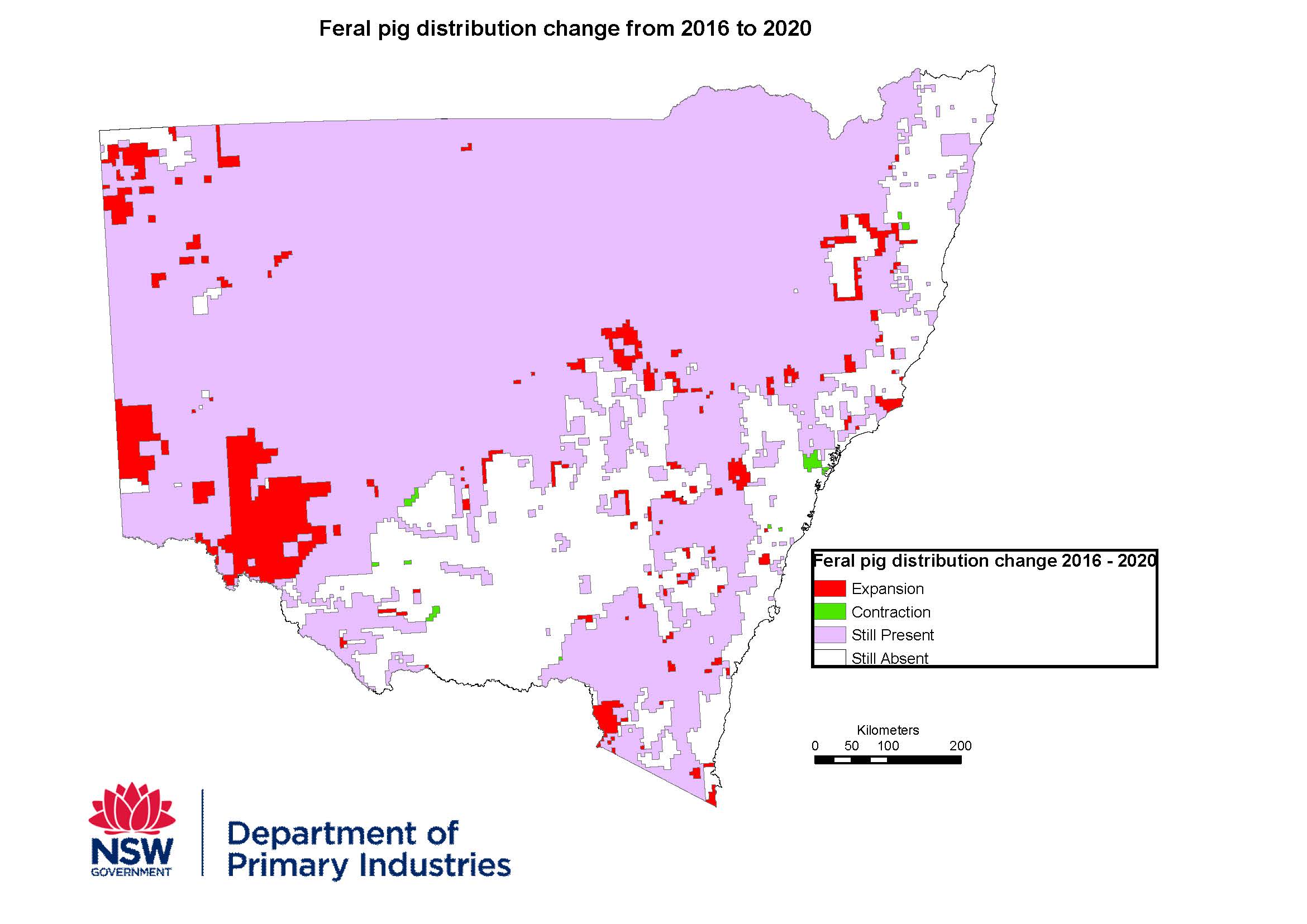

Feral pig distribution change from 2016 to 2020

More information

NSW

- NSW Code of Practice and Standard Operating procedures for the Effective and Humane Management of Feral Pigs

- NSW Vertebrate Pesticide Manual

- Local Land Services feral pig advice

- Regional Strategic Pest Animal Management Plans