Eastern King Prawn Habitat: Growing a fishery, naturally

The Eastern King Prawn (EKP) fishery is one of the most valuable fisheries in NSW. Despite this, little is known about the ecology of juvenile EKP during their time spent in NSW estuaries or about how habitat change has affected productivity.

Why we researched juvenile EKP habitat

We need to understand the habitat factors that affect prawn recruitment and survival in NSW estuaries. A research study in the USA has shown that a hectare of restored wetland habitat can contribute up to 60,000 prawns to the post-juvenile population. Based on this figure, it is estimated that similar habitat rehabilitation could increase the EKP fishery yield in NSW by about 425 kg per year for each hectare of rehabilitated habitat.

Improving our understanding of the habitat needs of juvenile EKP and the impact of habitat change, will enable us to work more effectively with both commercial fishers and coastal land managers to target restoration and rehabilitation activities to maximise fishery benefits.

What we knew

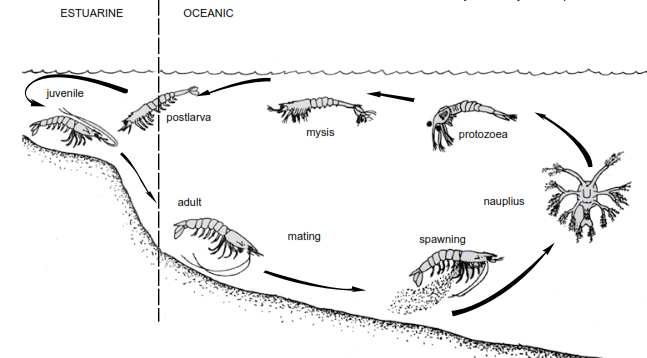

The Eastern King Prawn (Melicertus plebejus) is only found in the coastal regions of eastern Australia between central/northern Queensland and eastern Victoria. Its life cycle is relatively well-known - spawning predominantly occurs in deeper waters off northern NSW to Swains Reef in Queensland, and larvae develop as they drift south in the east Australian current. Post larval prawns recruit into the lower reaches of estuaries and leave the estuaries as late-juveniles. Prawns further develop in coastal habitats before reaching maturity and commencing a northward migration back to the northern spawning areas.

The estuaries of northern NSW are considered to be some of the most important recruitment areas for EKP. Commercial fishers have provided many anecdotal reports of the extensive use of estuarine swamps by young EKP prior to the loss of wetland areas through urban and agricultural development. Also, anecdotal information suggests the inundation of freshwater and subsequent lowering of salinities in estuarine nurseries has had an adverse effect on growth and abundance of prawns.

This research aims to help understand the linkages between EKP and coastal habitats, described by fishers, and guide our efforts to rehabilitate habitat in order to naturally increase the productivity of the EKP fishery.

Key Project Findings

Food + not too much freshwater + warm water is ideal.

Rapid declines in temperature and salinity are not good for EKP productivity.

An estuary is not one big habitat: prawns live in the patches where conditions are favourable.

Much of the food eaten by juvenile EKP is from saltmarsh habitats

- Ideal habitat areas are places within estuaries where there is a supply of food, the salinity isn’t too low, and the temperature isn’t too cold. Shallow sand flats with low currents and marsh channels that are submerged across all tides are ideal, particularly in the lower estuary.

- Stable temperature and salinity are best. Juvenile EKP do not like rapid declines in temperature and salinity levels, such as during flood events. More tend to die and the survivors generally don’t grow well. This helps explain why commercial fishers tend to notice fewer, and smaller, EKP in wetter years.

- An estuary has many different habitats. Where EKP are found seems to depend on currents, salinity, and food availability. In some estuaries, the juveniles are more abundant along the edges of shallow, muddy creeks near mangroves, while in others they were found mainly on seagrass beds.

- Young EKP have a varied diet, eating plant material, crustaceans, microorganisms, small shellfish, and worms. Much of their nutrition is derived from saltmarsh habitats and is transported to the subtidal waters where the prawns live.

- Estuaries need to be connected to wetlands, saltmarsh areas and floodplains. Cutting-off tidal flows and draining wetlands reduces food availability, which can impact on EKP populations. Restoration of more natural tidal flows is producing benefits for juvenile EKP.

- In the Hunter River estuary, in areas where natural tidal flows have been restored, EKP are now being found much further upstream, with strong recruitment occurring. This provides the first clear demonstration of the impact of restoring connectivity with estuarine wetlands for commercial species of prawns in NSW.

- In the Clarence River estuary, there were very few EKP found in the southern channels, despite there being abundant habitat and appropriate salinity. This could be because these areas are not well connected to incoming tides due to a large training wall. More natural tidal flow could boost the local EKP population in the southern channels.

- In Lake Macquarie, both wind and tide are important factors influencing habitat use by EKP. Habitat rehabilitation efforts do not usually take seasonal wind into account! For the EKP, seagrass rehabilitation efforts (such as replacement of swing boat moorings with environmentally friendly moorings) could improve habitat areas between 6 and 9 km from the estuary mouth to maximise benefits for EKP.

What the Project Involved

The project had the following objectives:

- Determine to what extent young EKP are using natural, degraded or rehabilitated habitat in estuaries, and the contribution of these habitats to the fishery.

- Determine the hydrographic conditions which provide for maximum growth and survival of EKP within nursery habitats.

- Determine the extent of key EKP habitat lost and remaining in a number of key estuaries between the Tweed and the Hawkesbury.

- Outline the potential improvements to the EKP fishery that could be achieved through targeted wetland rehabilitation and freshwater flow management.

- Extend information on EKP habitat requirements to commercial fishers, landowners and other catchment stakeholders and incorporate recommendations into fisheries or water management.

Researchers from NSW DPI Fisheries collaborated with researchers from Griffith University, University of Newcastle and University of NSW. The Principal Investigator and person to contact with any queries is: Dr Matt Taylor (NSW DPI Fisheries) on 02 4916 3937.

Learning from commercial fishers

EKP fishers provided valuable information about EKP habitat and how habitats have changed. In the first part of the project historical references were examined and discussions held with current and former commercial fishers in this fishery to build a picture of just how productive the fishery once was. In addition, EKP fishers responded to a short survey to inform future effective communication with them on the findings.

Funding

The project was supported by funding from the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation on behalf of the Australian Government, with significant in-kind support from NSW Department of Primary Industries. Additional funding was provided by the Hunter and the North Coast Local Land Services, as well as Hunter Water, the Newcastle Ports Corporation, and Origin Energy. The project was supported by the NSW Professional Fisherman's Association, the Newcastle Commercial Fishermen's Co-operative and Oceanwatch.

Project Resources

Eastern King Prawn Habitat - Growing your fishery, naturally: A project information brochure for commercial fishers.

- A4 - 4 pages, portrait (PDF, 1763.71 KB)

- A3 - 2 pages, landscape (PDF, 1485.56 KB) Print this landscape, double-sided to produce a fold-out brochure

Eastern King Prawn Habitat -Managing land to grow more prawns: A project information brochure for land managers

- A4 - 4 pages, portrait (PDF, 2571.76 KB)

- A3 - 2 pages, landscape (PDF, 1537.79 KB) Print this landscape, double-sided to produce a fold-out brochure

Eastern King Prawn Communication Plan (PDF, 665.68 KB)

Estuarine Habitat and Fishery Linkages Workshop Summary Report (PDF, 2014.71 KB)

Project updates are available below.

- EKP project update - November 2015

- EKP project update - July 2015

- EKP project update - November 2014

- EKP project update - June 2014

Published Papers and Presentations

Detailed research methodology and findings are available in the papers published in peer-reviewed journals. The following plain-English summaries include the publication details.

- A rapid approach to evaluate putative nursery sites for penaeid prawns (PDF, 137 KB)

- Nocturnal sampling reveals usage patterns of intertidal marsh and subtidal creeks by penaeid shrimp and other nekton in south-eastern Australia (PDF, 158.84 KB)

- Recruitment and connectivity influence the role of seagrass as a penaeid nursery habitat in a wave dominated estuary (PDF, 121.79 KB)

- The role of connectivity and physicochemical conditions in effective habitat of two exploited penaeid species (PDF, 202.29 KB)

- The economic value of fisheries harvest supported from saltmarsh and mangrove productivity in two temperate Australian estuaries (PDF, 161.81 KB)

- Direct and indirect interactions between lower estuarine mangrove and saltmarsh habitats and a commercially important penaeid shrimp (PDF, 169.07 KB)

Useful links

This section provides links to project partners, funders and sponsors. Also included are links to other organisations working on sustaining EKP fishery productivity through habitat rehabilitation. Visit the Useful links page.