Red meat and sustainable protein production

The farming of beef and sheep for red meat production is a major contributor to total greenhouse gas emissions from NSW agricultural systems. Sheep and cattle have digestive systems which produce a lot of methane, a greenhouse gas that is around 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. These emissions give red meat a high carbon footprint which has led to calls for reducing or stopping red meat production to reduce the climate change impacts of our diets.

What has not been well recognised in both academic and social media commentary has been the important role that sheep and cattle production play in the sustainable use of land and water resources. This article highlights some of these issues with the aim of encouraging a more nuanced discussion about the role of livestock in sustainable production systems. These include land suitability, sustainable crop rotations, crop wastage and livestock co-products.

Land suitability

Most agricultural land is not suitable for crop production due to either:

- low rainfall,

- excessive slope,

- vegetation that would need to cleared, and/or

- rocky/shallow soils

Only 20% of NSW land (excluding urban and conservation areas) is considered arable land suitable for cropping. Meeting growing global food demand by clearing land for crop production, or cropping unsuitable land, is likely to lead to land degradation and poor environmental outcomes.

Livestock predominantly graze non-arable land, including productive pastures on the southern highlands, tablelands of central and northern NSW, and rangelands of western NSW.

Through livestock production, non-arable land is used to supply high quality human-edible protein. With global population projected to reach 10 billion people by 2050, the most effective use of all land resources is a key consideration.

Sustainable crop rotations

Many farmers growing crops like wheat and barley also include legume (e.g. lucerne/clover) pastures in rotation with their crops. They then integrate livestock into their farming system to graze these rotational pastures. Legume pastures are beneficial because they increase soil nitrogen and carbon and can reduce the need for chemical fertilisers when the land is returned to cropping in the next rotation. Grazing legume pastures also has positive economic benefits because it reduces the variability of farm income in years when crops fail due to drought, frost, disease or flood.

Grain unsuitable for human consumption

Not all grain harvested is suitable for human consumption due to issues such as:

- low protein content,

- contamination with weed seed or foreign materials (e.g. soil, rocks), or

- weather damage.

In years with adverse weather events such as late frosts, moderate drought or excessive rainfall around harvest time, low quality grain can make up a substantial proportion of the harvest. This grain is fed to livestock to convert it to human-edible protein whereas grain suitable for human consumption in products such as pasta, beer or baked goods is generally too expensive to be fed to animals.

Crop wastage

Failed crops

Crops that are sown for human-edible protein can fail due to drought, disease and/or frost. Systems that integrate livestock utilise failed crops ensuring that the land and inputs used to grow the crop produces human edible-protein. Alternatively, failed crops can be used for hay or silage that can be stored and fed to livestock during times of low feed supply. Both of these options are high value uses for failed crops and result in the better utilisation of limited resources.

Spilt or unharvested grain

Grain can be spilt when a crop is harvested, sometimes up to 15% of the crop, as well as during transfer and transport. Further, crops sometimes cannot be readily harvested for a range of reasons (e.g. lodging, where the stems bend and the crop lies flat) or it is too wet for machinery to access). Livestock such as sheep are good for eating spilt or unharvested grain and can also reduce the reliance on herbicides by eating weeds and spilt grain that would otherwise germinate.

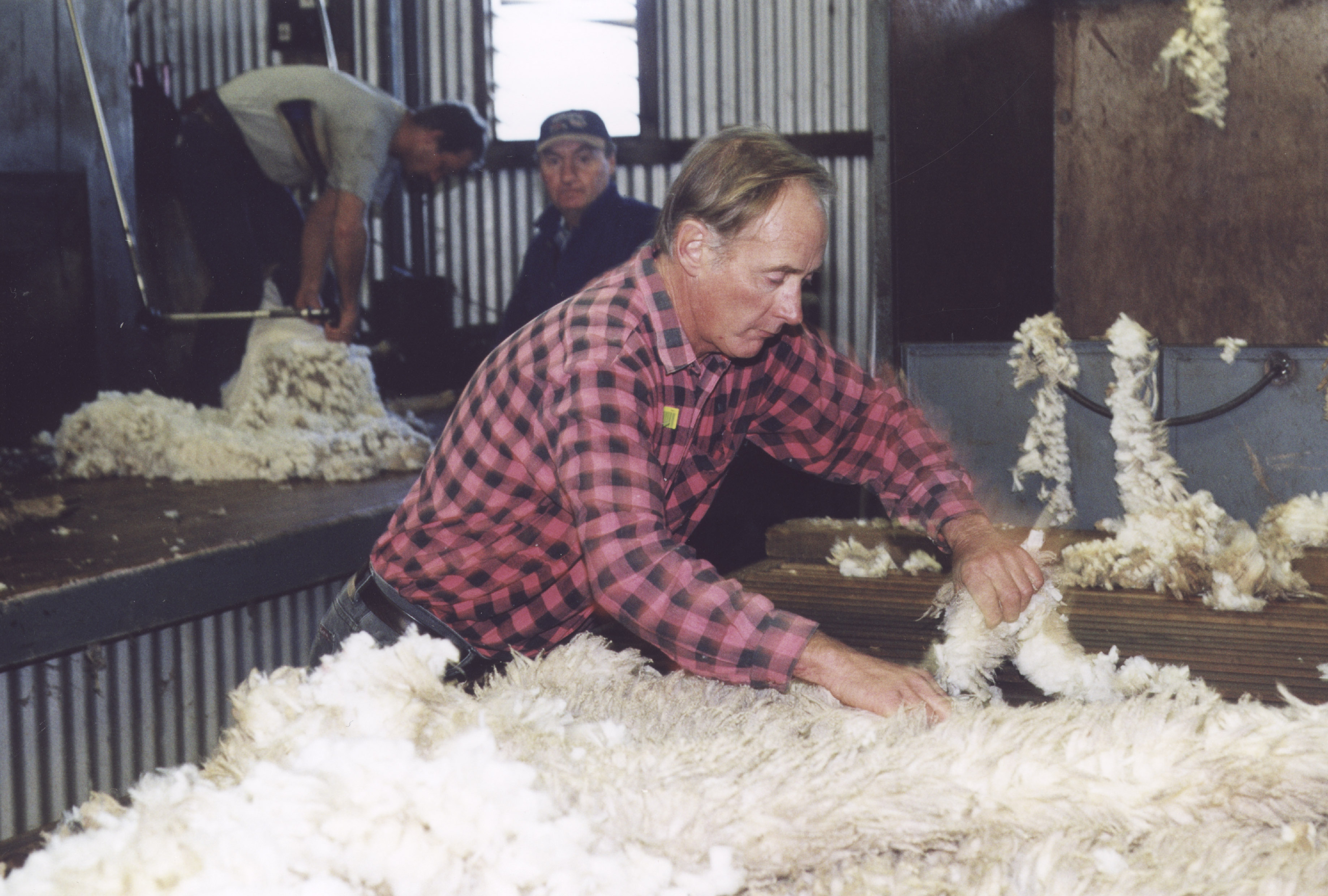

Livestock co-products

In addition to meat, livestock systems also produce co-products such as wool, leather, meat meal, tallow and dairy. If these products were not available from livestock systems substitutes would need be needed, for example synthetic fibres based on petroleum products, and plant-based milks that require arable land. The greenhouse gas emissions associated with producing these replacements need to be considered when assessing climate change impacts effects of red meat production.

Conclusion

There are many production efficiencies to be gained by utilising livestock in farming systems. They can graze land not suitable for cropping and also reduce waste in cropping systems. Claiming that significantly reducing or eliminating red meat production will result in positive climate change outcomes is overly simplistic. It does not consider the re-allocation of land and water to other production systems (e.g. land no longer grazed by livestock would be re-allocated to the next most profitable use) that would occur if livestock production systems were to change. Nor does it consider the climate change impacts of replacing the human-edible protein from livestock production systems, and their co-products, with functional equivalents. Livestock play an important role in sustainable agricultural systems by producing high-quality protein from land and biomass resources that would otherwise not be used for food production. Livestock relieve pressure and help sustain productivity of our limited cropland resources.

Contacts

Dr Aaron Simmons, Technical Specialist, Climate Research. aaron.simmons@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Dr Annette Cowie, Senior Principal Research Scientist, Climate Research. annette.cowie@dpi.nsw.gov.au