The dam

Size

The dam should have a surface area of at least 0.05 Ha (500 m2), preferably more.

Livestock access

Ideally, livestock should be excluded from dams stocked with fish, as they can damage dam walls and muddy the water. The best approach is to completely fence the dam, and provide an external trough with pumped or gravity fed water, although this may not always be practical. An alternative is to partially fence the dam, and restrict stock access to a narrow entry. Planting the fenced area with grasses, shrubs and trees has several benefits. Planting can improve the dam’s appearance and stabilise its banks, whilst decaying leaves provide nutrients to enhance the dam’s food chain, and falling insects are preyed upon by fish. Do not grow trees or shrubs on the embankment or spillway as they can disturb the dam structure.

Location

It is illegal to permit fish to escape from a dam. Dams that are likely to flood (as in a gully) should not be stocked, as it can be hard to prevent fish escaping. As well as reducing production in the dam, escaped fish can cause major problems in local river systems, especially if they are not native to the local area. NSW DPI recommends that dams on the eastern drainage (east of the Great Dividing Range) are located above the 1 in 100 year flood level while damns on the western range (west of the Great Dividing Range) should be constructed to avoid being inundated by the 1 in 100 year flood level. This is to ensure that stocked fish will not escape to surrounding waterways in a flooding event.

Ease of maintenance

Consider installing a pipe and gate-valve in a new dam, so that it may be drained from the bottom. This allows poor quality water to be drained easily, and complete drainage helps in dam maintenance (the site must have some slope). Drained water should not enter adjacent waterways.

Preparing the dam

Consider removing pest plants and fish from an existing dam before restocking. New dams should be filled and ‘aged’ for at least three months before stocking. This gives the food chain time to develop, and can be assisted by adding locally native water plants, shrimps and yabbies from other dams or other sources.

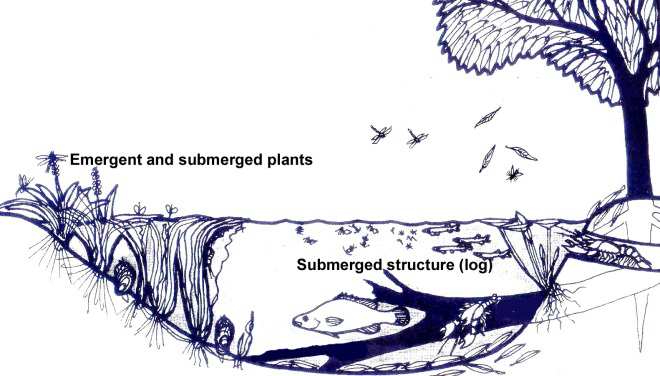

An ideal dam is one that mimics a natural wetland, providing plant growth, structure, shade and food.

Note. A permit may be needed to build your dam. A NSW DPIRD permit may be required to collect organisms to put in farm dams. Some species are illegal to stock in your dam.

Water quality

Comprehensive water tests are expensive and are generally not needed for farm dams. Most surface and bore water suitable for irrigation or stock is acceptable for fish. A small test stocking will quickly show whether the water is suitable.

Muddy water may not harm native fishes directly but it can lower food production by preventing light penetration. On the other hand, some turbidity can help reduce predation by making the fish hard to detect by predators.

Species to avoid

Species to avoid

Some fish species (which are listed as prohibited or notifiable species in NSW) are illegal to stock into farm dams. For the latest list of noxious fish, visit the NSW DPIRD Fisheries website.

Many exotic species, even if they are not illegal, are undesirable, either because of their effects on the dam or because of their risk to the natural environment if they escape. More information on some of these undesirable species can be found later under ‘Potential problems’.

There are good reasons for stocking fish that occur naturally in your area.

- Local fish are well adapted to the environmental conditions, and likely to survive well in your dam, provided they are not predated upon.

- Suitable local fish are frequently available from the nearest hatchery.

- If exotic fish are stocked and escape into the wild, they can become serious pests which compete with native species and cause environmental damage. This can apply even to stocking native fish from a different part of NSW or Australia.

Also take care to buy only native water plants for your dam. Many exotic plants can not only choke your dam but may end up spreading and blanketing local rivers.

Suitable species

Fry and fingerlings are available from licensed hatcheries throughout the State. See the Aquaculture Industry Directory.

Australian native fish

Most native fish species are native either to the coastal drainages or to western NSW. In general, fish from one region should not be stocked into the other. Exceptions to this rule are noted below.

Suited to the coastal and inland plains and the lower slopes of the Great Dividing Range, most native species can tolerate water temperatures of 4–30ºC. The catfish, and perhaps the Silver Perch and the Murray Cod, occasionally breed in dams; however, the young often die from inadequate food, parasites, or through predation by insects, birds and other fish. Some fish need complex environmental stimuli not easily reproduced in farm dams.

Silver Perch (Bidyanus bidyanus)

Native to the western drainage (Murray–Darling Basin). Wild (river) populations are listed as a ‘vulnerable’ species and are protected, although they have been stocked in many dams for angling. Silver Perch may be the best warm water fish for stocking in western drainage dams, because it is an omnivore (eats both animal and plant matter): it lives on shrimps, insects, plankton and algae, and so can exploit a greater range of food sources than the carnivorous fishes. Good to angle and excellent to eat, it can reach plate size within two years. Stocking of Silver Perch in dams on the eastern drainage is not encouraged unless there is no chance of escape into local waters.

Golden Perch (Macquaria ambigua)

Native to the western drainage (Murray–Darling Basin), this is an excellent angling and table fish. In warm areas where food is plentiful, it may reach eating size within a year, but usually takes two years. It is a carnivore, feeding on yabbies, insects, shrimps and small fish. Because of its different diet, it may be stocked together with Silver Perch. Stocking of Golden Perch in dams on the eastern drainage is not encouraged unless there is no chance of escape into local waters.

Australian Bass (Macquaria novemaculeata)

Native to coastal streams of the eastern drainage. It is one of the best known recreational freshwater sportfish, as well as being excellent to eat. Its diet includes a wide range of fish, yabbies, shrimps and insects, and it adapts well to farm dams. It can exceed 4 kg in dams, but cannot breed there. Australian Bass are the preferred fish for farm dams on the eastern drainage of the Great Dividing Range. They should not be stocked into western drainage dams.

Eel Tailed Catfish (Tandanus tandanus)

A hardy species native to both coastal and western drainages, although research has shown that there are several sub-species, with those east of the Great Dividing Range being different from those in the west. A good angling and eating fish, although commonly rejected because of its appearance. It is carnivorous, feeding on shrimps, yabbies and insects. It can be stocked with other species, and reaches table size in 2 years. It matures at 5 years, and builds metre- wide stony nests for breeding in spring–summer (when water temperatures reach about 24ºC). Their venomous spines can inflict painful wounds.

Catfish to be stocked should be obtained locally to ensure that the various sub-species do not hybridise.

Murray Cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii)

Native to the western drainage (Murray–Darling Basin). It is the largest Australian freshwater fish: 5–10 kg is not uncommon, and individuals of 30 kg are caught occasionally. The record is 113.5 kg and 1.8 m (Barwon River, Walgett). The Murray Cod matures at 5–6 years, and may breed in farm dams if there are hollow logs or drums where it can deposit its eggs. A carnivore, it eats insects, yabbies, shrimps and fish. It is ready for the table after 2 years, and makes an excellent dish. The Murray Cod is aggressive and territorial. Once an individual grows a little larger than others within its area, it has a competitive edge for food, resulting in a wide separation in sizes in the dam, which can lower overall survival. Other sport fish should not be stocked with them.

It is illegal to stock Murray Cod into farm dams in north-eastern NSW, draining east of the Great Dividing Range north of the Waterfall Highway between Urunga and Armidale, as it could compete or hybridise with the endangered eastern freshwater cod. Stocking of Murray Cod in dams on the eastern drainage is not encouraged unless there is no chance of escape into local waters.

Introduced fish

Trout are introduced species that have the potential to negatively impact on native fish. They should only be stocked into regions that have previously been stocked with trout, in dams that preclude escape into public water bodies.

Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) and Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) grow well in farm dams.

The Rainbow Trout is probably the best of these for farm dams as it is the fastest grower and most easily caught. It can reach 2 kg in 2– 3 years and is excellent for both angling and eating. Trout cannot breed in farm dams as they require running water and gravel beds to spawn. Suitable for dams on the upper slopes and highlands, where summer water temperature does not exceed 20ºC (measured 50 cm below the surface).

Freshwater Crayfish

About 100 species of freshwater crayfish are native to Australia. They vary in their habitat and food requirements and should generally be stocked only in areas where they occur naturally – the possible effects on local crayfish and other animals and ecology are unknown, and it can be very difficult to prevent the escape of crayfish from dams.

The common yabby (Cherax destructor) is native to the western drainage in NSW. It is found in many permanent and semi-permanent waters and is easy to catch. The yabby is sometimes used as food for farmed fish but is fast becoming a culinary delight in restaurants across Australia. Yabbies can be produced in farm dams but should not be stocked with fish if they are to be the main crop. A suitable number for seeding a 0.1 ha dam would be 20–

40. If seeded in spring (breeding time), the dam should produce enough for limited fishing within two years.

Several other species of Cherax occur along the coast from Newcastle northwards, but little is known of their biology or suitability for farming. The common yabby should be stocked only in farm dams in the western drainage. Eastern drainage farm dams should be stocked only with yabbies collected locally. However, local crayfish may naturally colonise farm dams.

The marron (Cherax tenuimanus) from Western Australia and the Queensland Red-Claw (Cherax quadricarinatus) must not be stocked in farm dams in NSW. Licensed aquaculturists exempt under strict biosecurity conditions applied to their aquaculture permit. The spiny crayfishes (genus Euastacus), including the Murray Crayfish and the Sydney Crayfish, are unsuitable for farming. They need cool, clean, well oxygenated water, and cannot survive long in most farm dams.

Stocking rates

The carrying capacity of a dam (i.e. the maximum weight of fish it can support) depends on the amount of food produced, size of the dam, water quality, species of fish and other factors.

Carrying capacity is generally independent of water depth, as food is usually produced in the water near the surface. The stocking rate is therefore calculated from surface area alone, ignoring depth and volume.

Typically, NSW farm dams have a carrying capacity of 200–500 kg/ha. This means that a 0.1 ha dam with a carrying capacity of about 500 kg/ha would support about 50 fish averaging 1 kg, or 25 fish of 2 kg each. At higher densities, growth slows. Maximum production can be maintained by removing small numbers of fish as required.

The following table gives recommended numbers of each species to stock in farm dams of different sizes. To estimate the size, count the number of long paces around the dam; this is approximately equal to the perimeter in metres. If several species are to be stocked together, the quantity of each should be calculated as a fraction of the total.

Dam size | Number of fish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perimieter (metres) | Surface area (ha) | Silver Perchand Catfish | Golden Perch and Australian Bass | Murray Cod and Trout | |

100 | 0.04 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

150 | 0.11 | 50 | 25 | 25 | |

200 | 0.22 | 75 | 50 | 25 | |

250 | 0.37 | 125 | 100 | 50 | |

300 | 0.54 | 200 | 125 | 75 | |

325 | 0.64 | 225 | 150 | 100 | |

350 | 0.75 | 275 | 200 | 125 | |

375 | 1.00 | 350 | 250 | 150 | |

Fish stocking, survival, growth and feeding

Releasing fish

When releasing fish, sit the bag in the dam water for 10 minutes to let the ambient temperature adjust to prevent thermal shock. Then open the bag and let in small amounts of dam water over 20 minutes, so that there is no sudden change in temperature or water chemistry. If possible, liberate the fish near cover (in reeds).

Survival and growth

Native fishes are usually 3–5 cm long when sold and trout 7–10 cm. Provided the dam is free of predatory fish and birds, there is little advantage in stocking larger fish. Survival is usually around 70%, but far less if predators are present. Growth rates vary a lot and cannot be predicted without a good understanding of conditions in the dam. At the recommended stocking rates, fingerlings commonly reach 100–500 g in the first year.

Food

The natural food for fish in farm dams is plankton, insects and yabbies. Animals that are not usually found in farm dams, such as freshwater shrimp and small fishes, can be added; they will breed and increase the food supply. Shrimp caught with scoop nets from permanent streams and lakes can breed to large numbers in dams with aquatic plants.

Small, locally sourced native fishes such as gudgeons and smelt, or even Bony Bream, can supplement natural food. Care must be taken to not introduce pest fish that may escape into natural waterways.

Inorganic fertilisers are not usually needed, as nutrients are often plentiful in farm dams. The food chain, including plant growth, usually depends more on light penetration and algae production. Supplementary feeding with artificial food is not recommended. Uneaten food can decay and pollute the water, resulting in poor water quality, disease, and excessive plant and algae growth.

Potential problems

Predatory birds

Cormorants are common throughout NSW, even in dry inland areas. Their visits to dams are infrequent and unpredictable, but once a dam containing fish is located, the birds work it until they have taken most of the fish. Even if prevented from landing on the water, cormorants will land on the bank and walk in. They are the most prodigious predators of fish in dams and soon learn to ignore scare devices.

Shooting them is prohibited, as they are protected in NSW.

There is no simple single method of control, and a combination of methods may be the best. Provide refuges under the water, such as fallen timber and submerged aquatic plants, to give fish some cover and protection from birds. (Where dams are regularly de-silted, such refuges must be portable).

Provide plenty of alternative food for the cormorants. Large numbers of yabbies, shrimp and small fish in a dam will lessen the predator pressure on the stocked fish, as the birds will prey on the most abundant food source.

Other birds (pelicans, and wading birds, such as herons and egrets) do not pose much of a problem, except in shallow dams. These birds are also protected. Ducks are essentially herbivorous and therefore harmless.

Undesirable fish

Tilapia

Tilapia are farmed in Africa, Israel and throughout South-East Asia, but their introduction or escape to streams is disastrous for native fishes and for stream or lake ecology. In countries where they have been introduced, tilapia have eliminated many native fishes, or threaten them with extinction.

Tilapia are very hardy, and can survive in conditions that kill other fish. They are prolific breeders and mouth-brooders (i.e. the female protects the eggs and fry by holding them in the mouth); this ensures high survival of the young. They are herbivores, but grow rapidly and compete aggressively with native fishes, attacking and nipping their fins.

A number of tilapia species have been accidentally released into NSW waters, and one species is quickly becoming widespread in Queensland and Western Australia. Three species are listed as prohibited or notifiable species in NSW and it is illegal to possess them or stock them into farm dams.

Eastern gambusia (Gambusia holbrookii)

Often incorrectly called a ‘guppy’, Eastern gambusia is a small livebearer with high survival of the young.

They are aggressive, nip the fins of larger species, and out-compete gudgeons, perches, galaxias and other small native fishes. Wherever there is gambusia, few young of other species survive. Since gambusia can destroy many fingerlings, they should be removed if possible.

Eastern gambusia is listed as noxious and are illegal in most of NSW.

Redfin Perch (Perca fluviatilis)

Redfin Perch are aggressive and prey heavily on fry and juveniles. They also carry a virus detrimental to some native fishes and trout, and a tapeworm that can infect humans. In dams, they breed readily and can overpopulate the dam, producing a large number of stunted individuals.

Carp (Cyprinus carpio)

Carp are a large fish (to 1 m) with large scales, and two pairs of barbells near the mouth. They are not great predators, but are known for out- competing native fish and surviving in poor conditions. Carp have proven capable of invading new waterways very quickly, and are renowned for muddying streams and eroding banks. The Koi Carp is an ornamental variety of the same species.

Eels (Anguilla australis & A. reinhardtii)

Eels are common in farm dams on the coastal side of the Great Dividing Range. Eels are real survivors, and will prey heavily upon young fingerlings.

Eels spawn at sea, and the young (elvers) migrate to freshwater in spring and summer, then upstream to the headwaters. Adults and young enter farm dams at night, moving over grass wet with dew or rain. Eels are attracted to lights and are readily caught using fresh meat. A few nights of hard fishing can usually rid a dam of eels.

Excessive plant growth

Plants provide food and shelter for insects and shrimp, and also for stocked fish, but too much plant growth can hinder fishing. If plants die in large quantities (due, for example, to spraying or winter die-off), the decay will cause massive oxygen depletion. Fish, and even the whole food chain, can be destroyed.

Excessive plant growth is mainly due to an overload of nutrients entering the dam. The best way to prevent such growth is to exclude nutrients. Bypass any waste and run-off from dairies, piggeries, cattle yards and fertiliser stockpiles. Even run-off from heavily fertilised pasture can cause nutrient problems. If you cannot prevent nutrients entering the dam, then plants may have to be removed mechanically or controlled with chemicals.

Mechanical control. The simplest and least harmful method in full dams is to remove the plants with a rake or a dragline, but this is practical only in small dams. Another way is to drain the dam completely and either remove the plants or let them die. (Note. Filamentous (stringy) green algae will quickly re-colonise a dam if even a green tinge remains).

Lack of oxygen

Low dissolved oxygen is a common problem in farm dams in summer, especially after rain, when organic matter (dead grass and animal droppings) has been washed into the dam. The first sign is usually dead fish, or dying fish which appear at the surface gasping for air.

The water must be circulated to expose the deeper water to the air. It is best pumped from the bottom and sprayed into the air. The water body can often be ‘turned over’ simply by hosing the surface with a fine spray; the cool surface layer will eventually sink bringing the deep water to the top, where it becomes re-oxygenated.

Harvesting fish

Recreational angling laws must be followed, even on your own property. It is illegal to harvest a pond with a net, unless a permit is held. If in doubt, refer to the website or contact your local Fisheries Officer.

Some fish develop off-flavours from blue-green algae. The taste can be removed by holding live fish for several days in clean aerated water or a 5g/L salt solution.

Further reading

There are not many texts on management of small ponds and farm dams under Australian conditions. The following publications give general information on fish biology, aquaculture and overseas techniques.

Allen, G.R. Freshwater fishes of Australia. TFH Publications, Neptune City, NJ USW, 1989

Fallu, R. Fish for farm dams. Agmedia, Department of Agriculture, Victoria

Johnson, H.T. The freshwater yabby. Fishfacts 2. NSW Fisheries, Sydney, 1993

McDowall, R.M. (Ed). Freshwater fishes of South- eastern Australia. Reed, Sydney, 1993

Merrick, J.R. and Schmida, G.E. Australian freshwater fishes; biology and management. Griffin Press, Adelaide, 1984

Smith, L.W. and Trounce, R.B. Aquatic weed control in small dams and waterways. Agfact P7.2.1 2nd Ed. NSW Agriculture 1992

Owen, P. and Bowden, J (eds) Aquaculture in Australia: fish farming for profit. Rural Press, Brisbane, 1986

Rowland, S.J Murray Cod (Maccullochella peeli). Agfact F3.2.4. NSW Fisheries, Sydney 1988

Williams, W.D. (Ed) An ecological basis for water resources management. ANU Press, Canberra, 1980 (Several chapters, including ‘Aquaculture’ by N.M. Morrissy and ‘Farm dams’ by B.V. Timms) Williams, W.D, Life in inland waters. Blackwell Scientific, Melbourne, 1983