Why are tilapia a risk to native fish and habitats?

Characteristics allow tilapia to establish in new areas include:

- Highly efficient breeding strategies including mouth brooding.

- Simple food requirements (feeding on a wide variety of plant and animal matter).

- Flexible habitat preferences (including the ability to breed in both fresh and brackish water).

Impacts tilapia have on native fish and habitats include:

- Competition with native species for food and space.

- Predation upon the eggs and young of native species.

- Aggressive behaviour of tilapia can lead to poor condition and higher infection and mortality rates for native species.

- Nest building by male tilapia may also damage aquatic habitats through damage to aquatic vegetation and increased turbidity.

Where are tilapia found in NSW and elsewhere in Australia?

In 2014, the first established population of tilapia in NSW was confirmed at Cudgen Lake near Cabarita Beach on the NSW far north coast. The species is Oreochromis mossambicus (Mozambique tilapia).

Three species of tilapia - Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus), spotted tilapia (Pelmatolapia mariae) and redbelly tilapia (Coptodon zillii) - have established successful breeding populations at several sites in Queensland, Victoria and Western Australia. Populations of Mozambique tilapia within southern Queensland are as little as 3 km from the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB). Tilapia pose a significant threat to the native fish of the MDB. For more information on the distribution of tilapia in Australia, see Species of tilapia found in Australian waters.

Where did tilapia come from?

Tilapia are native to warm, fresh and brackish waters of Africa, South and Central America, southern India and Sri Lanka. Tilapia were historically imported to be kept as aquarium fish. Due to the significant risk these fish pose to native fish and the environment they are now listed as a notifiable pest under NSW legislation meaning it is illegal to possess, sell or move tilapia.

What is NSW DPIRD doing?

NSW DPIRD works with other government agencies, non-government agencies, industry and the community to minimise the risks of tilapia spreading and establishing throughout NSW. This approach recognises that biosecurity is a shared responsibility.

NSW DPIRD:

- Maintains legislation regarding notifiable species such as tilapia

- Monitors fish populations in coastal and inland rivers in NSW

- Prepares for potential incursions of pest species

- Responds to reported sightings of pest species, including tilapia

- Works to raise awareness of pest species, including through collaboration with local government and environmental organisations (e.g. advisory materials, workshops, media releases).

- In 2023, we released the Tilapia Control Plan . It sets goals, priorities and actions to improve NSW’s overall ability to prevent and respond to new tilapia incursions and manage the negative impacts of established populations

General Biosecurity Duty

Under Biosecurity legislation, all community members in NSW have a general biosecurity duty to consider how actions, or in some cases lack of action, could have a negative impact on another person, business enterprise, animal or the environment. We must then take all reasonable and practical measures to prevent or minimise the potential impacts of pests and diseases.

How you can help stop the spread of tilapia

Tilapia infestations are usually caused by people moving the fish between waterways. Help stop this spread with the following guidelines:

- Don’t release fish into waters or allow fish to escape into waterways. It is illegal to return any recreationally caught tilapia to the water. If caught whilst recreational angling they must be humanely dispatched and utilised or disposed of in a bin going to landfill.

- Don’t use suspected pest species as bait (whether dead or alive). Even dead tilapia may still have eggs or young in their mouths.

- Obtain a permit from NSW DPIRD prior to any fish stocking activities and stock fish from a reputable local supplier rather than another region or interstate (to minimise risks of introducing species not native to your local area). Note - it is illegal to release fish into waters without a permit and heavy penalties apply.

- Give unwanted aquarium fish to a friend or a pet shop. If a suitable home cannot be found, please see the recommended guidelines for humane destruction of fish.

- Learn how to identify tilapia.

- Be on the lookout for new species of fish in your area.

- Report sightings of suspected tilapia, take good quality photographs and freeze the whole fish where possible.

- Clean your gear (PDF, 385.23 KB) (e.g. landing nets, boots) and check for signs of eggs or young tilapia. If found, ensure these eggs and young are not able to re-enter any NSW waters.

How to identify tilapia

- Tilapia vary in colour from dark olive to silver-grey, depending on their age and environment.

- They are generally deep-bodied fish with thin profiles, long snouts and pronounced lips/jaws.

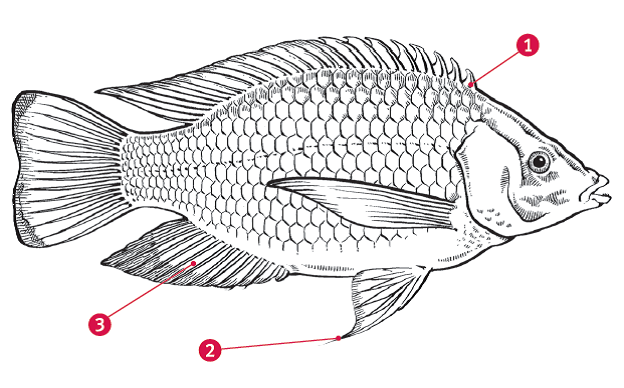

- Their dorsal (upper) fin (1) is continuous and ends in an extended point. Most native species have a dorsal fin with a dent/gap in the middle and a rounded end.

- Their pelvic (belly) fins (2) are long and almost touch the front of the anal (bottom) fin (3). This is unlike most native species, which have short pelvic fins.

Species of Tilapia found in Australian waters

Mozambique tilapia

Of all the tilapia species, the Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) has the most widely distributed feral populations in Australia. It is also the species of tilapia most at risk of entering the Murray-Darling Basin, with populations as little as 3 km from this river system in southern Queensland.

Mozambique tilapia can grow to more than 36 cm in length and live for up to 13 years. However, size varies according to environmental conditions, with poor conditions sometimes producing many small (but still mature) fish.

Tilapia can become sexually mature less than one year in ideal conditions. This equates to a fish around 15 cm long, although stunted fish can breed at 9 cm. Breeding males become very dark (almost black) with red edging on their fins.

After spawning, the female takes the eggs in her mouth, where they hatch - the fry remain in their mother's mouth for up to 14 days before they are released, and may remain near the mother and re-enter the mouth when threatened until about three weeks old, thus receiving protection from predators. This strategy is known as mouth brooding.

Mozambique tilapia are hardy fish, tolerating a wide range of temperatures and surviving in high salinities and low dissolved oxygen. Consequently, they have colonised a variety of habitats including reservoirs, lakes, ponds, rivers, creeks, drains, swamps and tidal creeks. They usually live in mud bottomed, well-vegetated areas, and are often seen in loose aggregations or small schools.

Spotted tilapia

Spotted tilapia (Pelmatolapia mariae), also known as Black Mangrove Cichlids, are found in northern Queensland waters around the Cairns region. They have also established a self-sustaining population in the heated waters of the Hazelwood power station pondage near Morwell in Victoria.

Spotted tilapia grow to around 30 cm in length. They become sexually mature at about 10 to 15 cm. They prefer to spawn on hard substrates (such as logs), which they clean beforehand. They do not build nests and are not mouth brooders, but the eggs and fry are carefully guarded by one or both parents. The parents continue to care for the young until they are about 2-3 cm.

Spotted tilapia are less tolerant of cooler temperatures than Mozambique tilapia.

Their diet consists mainly of plants, although it appears they also eat animals when there is limited aquatic vegetation available.

Redbelly tilapia

Redbelly tilapia (Coptodon zillii), also known as Zille’s cichlid, are another species considered to be a potential threat if introduced into NSW waterways. An outbreak of redbelly tilapia occurred near Perth in Western Australia in 1975, but was eradicated by the state fisheries department.

They are normally found in sheltered waters over rock, sand or mud, including shallow pools, lagoons and the margins of rivers.

Commonly misidentified species

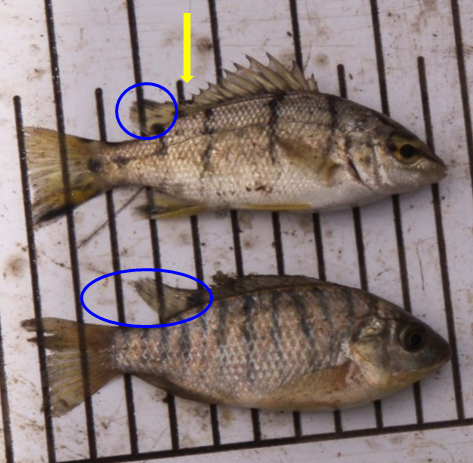

Banded grunter (notifiable fish species under Biosecurity legislation)

The major differences between Banded grunter (Amniataba percoides), also known as barred grunter, and tilapia include:

- Banded grunter have a dent separating the front of the dorsal (upper) fin from the back of the fin

- The end of the dorsal (upper) fin on a banded grunter is rounded

Please note that banded grunter are listed as notifiable in all waters of NSW.

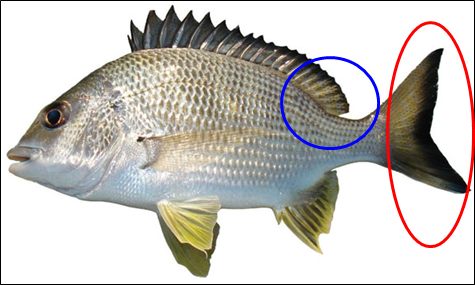

Bream

The major differences between bream (Acanthopagrus spp.) and tilapia include:

- Bream have a forked caudal (tail) fin

- The end of the dorsal (upper) fin on bream is rounded.

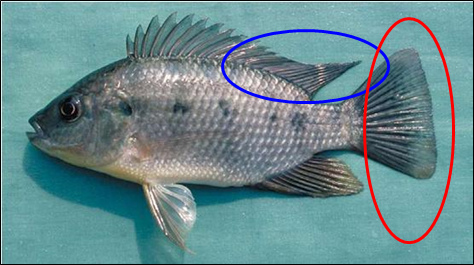

Juvenile silver perch

The major differences between juvenile silver perch and tilapia include:

- Juvenile silver perch have a longer, skinnier body shape.

- Silver perch have a dent separating the front of the dorsal (upper) fin from the back of this fin.

- The end of the dorsal (upper) fin on a silver perch is rounded.

Silver perch have a forked caudal (tail) fin.

References

Allen GR, Midgley SH, Allen M. (2002). Freshwater Fishes of Australia. Western Australian Museum, Perth.

Arthington AH, Bluhdorn DR. (1994). Distribution, genetics, ecology and status of the introduced cichlid, Oreochromis mossambicus, in Australia. Internationale Vereinigung fur theoretische und angewandte Limnologie/Communications 24: 53-62.

Condamine Alliance. 2014. Implementing the Northern Murray-Darling Basin Tilapia Exclusion Strategy – Final Report.Project to Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Queensland.

Hutchison M., Safac Z., and Norris A – Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation [2011]. Mozambique Tilapia. The potential for Mozambique Tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus to invade the Murray-Darling Basin and the likely impacts: a review of existing information. Murray-Darling Basin Authority under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence.

Lever C. (1996). Naturalized Fishes of the World. Academic Press, San Diego.

McDowall R. (Ed) (1996). Freshwater Fishes of South-Eastern Australia. Reed Books, Australia.