Pacific Oyster

Introduction

The Pacific Oyster (Magellana gigas) is endemic to Japan. It has been introduced into a large number of other countries outside its natural range including Australia. Most of these introductions have been for the purposes of aquaculture. Worldwide, Pacific Oysters are one of the most widely cultured shellfish species.

The Pacific Oyster (Magellana gigas) is endemic to Japan. It has been introduced into a large number of other countries outside its natural range including Australia. Most of these introductions have been for the purposes of aquaculture. Worldwide, Pacific Oysters are one of the most widely cultured shellfish species.

Pacific Oysters were first introduced into south-eastern and western Australian waters for aquaculture in the 1940s. In the 1980s they found their way into NSW waters, where they have spread and invaded intertidal habitats of many coastal waterways.

Pacific Oysters are a hardy species with fast growth and high reproductive rates. This has allowed them to establish dense populations in some areas, often displacing native intertidal species.

Since the 1990s Pacific Oysters have been the basis of an important aquaculture industry in Port Stephens, but elsewhere in NSW they have caused significant problems for oyster farmers who culture native Sydney Rock Oysters (Saccostrea glomerata). As the two species live and spawn in the same locations, Pacific Oysters can settle on and (due to their faster growth rate) smother farmed Sydney Rock Oysters.

Natural distribution & biology

Pacific Oysters are bivalve molluscs belonging to the family Ostreidae. They are native to northeast Asia (including Japan), but have been translocated and spread widely throughout many countries (including the UK, France, USA, Canada, Korea, China and New Zealand) for the purpose of aquaculture.

Pacific Oysters have a thin shell, with no hinge teeth inside the upper shell (unlike Sydney Rock Oysters). The adductor muscle (which holds the two shells together) is purple or brown in colour, whilst the edges of the mantle (the tissue which secretes and lines the shell) are black. Despite these distinct differences, it is difficult for the untrained eye to distinguish between the introduced Pacific Oyster and the native Sydney Rock Oyster.

Adult Pacific Oysters are sessile and can be found on a variety of hard substrates in the intertidal and shallow subtidal zones, to a depth of about 3 metres. They favour brackish waters in sheltered estuaries, although they tolerate a wide range of salinities and water quality and can also occur offshore.

Pacific Oysters have very high growth rates (they can grow to over 75 mm in their first 18 months) and high rates of reproduction.

Like most oyster species, Pacific Oysters change sex during their life, usually spawning first as a male and later as a female. Spawning is temperature dependent and generally occurs in the summer months. Female Pacific Oysters are highly fecund and can produce up to 40 million eggs per spawning, giving the surrounding water a milky appearance. Fertilisation takes place in the water column.

The larvae are planktonic and free swimming, developing for three to four weeks before finding a suitable clean hard surface to settle on. Although they usually attach to rocks, they can also settle in muddy or sandy areas (where they attach to small stones, shell fragments or other debris) or on top of other adult oysters. A very small percentage of oysters survive this phase; and once settled they are called "spat".

Pacific Oysters can live up to 10 years and reach an average size of 150-200 mm. Pacific Oysters are plankton feeders that filter minute marine algae and other microorganisms out of the water.

Where are they in NSW?

A survey of 30 oyster farming estuaries in NSW was undertaken in 2010 (NB: Brunswick River was also surveyed in 2012) to determine the distribution and abundance of wild Pacific Oysters within oyster producing estuaries of NSW. The survey design ensured comparison with previously completed Pacific Oyster surveys. The NSW Pacific oyster survey 2010 gathered information regarding the current known locations of established populations of Pacific Oysters on both cultivation and natural habitats occurring within each estuary. The 2010 survey found populations of Pacific Oysters in all estuaries south of and including the Hastings River.

Due to very high densities of Pacific Oysters in Port Stephens, Pacific Oyster culture has been permitted since 1990.

Following the impact on Sydney Rock Oyster farming of QX disease, the farming of functionally sterile triploid Pacific Oysters is enabled under permit in the Georges River and Hawkesbury River. Trial cultivation of triploid Pacific Oysters is also underway in a number of other NSW estuaries. More information regarding this can be found on our Aquaculture Pages.

In 2010/2011 an outbreak of Pacific Oyster Mortality Syndrome (POMS) impacted populations of wild Pacific Oysters in Port Jackson/Sydney Harbour and wild and farmed triploid Pacific Oysters in Georges River/Botany Bay. In early 2013, POMS was detected in farmed triploid Pacific Oysters in Hawkesbury River.

How did they get here?

Pacific Oysters were introduced deliberately into Western Australia and Tasmania in 1947, into Victoria in 1953 and into South Australia in 1969. The Pacific Oysters that were introduced in Tasmania and Victoria successfully spawned, however those introduced to Western Australia eventually died out.

Although Pacific Oysters were not brought legally into NSW, it is suspected that small numbers were introduced deliberately and they formed small populations in some NSW estuaries. Once established, Pacific Oysters were spread to other areas, possibly in part by mixing with Sydney Rock Oysters that were moved between estuaries by oyster farmers.

What are their impacts?

Once established, Pacific Oysters are generally impossible to contain if environmental conditions are suitable. Their planktonic eggs and larvae facilitate natural dispersal, and this in combination with high fecundity allows rapid population extension.

Pacific Oysters have the ability to develop high density populations within the intertidal zone. This has led to the competition between Pacific Oysters and other native species for food and space. In some areas Pacific Oysters have become the dominant oyster species, displacing native species such as Sydney Rock Oysters.

Native Sydney Rock Oysters are a prized seafood species and are the main focus of oyster production in NSW, comprising 88% of total oyster production in NSW during 2012-2013 (NSW DPI, 2014). The spread of Pacific Oysters, and their ability to displace (or even smother) native species, is an ongoing and major concern for NSW oyster farmers who cultivate Sydney Rock Oysters.

This change in the species balance also has the potential to impact on non-oyster species, through a modification of habitat.

What is NSW DPIRD doing?

Pacific Oysters have been listed as a Class 2 Noxious Fish in all NSW waters except Port Stephens under the Fisheries Management Act 1994 (Schedule 6C). The possession and sale of Pacific Oysters may only occur under a specific permit issued by NSW DPIRD.

The Class 2 listing recognises that farming of Pacific Oysters is a major and well-established industry in Port Stephens, worth around $1.5 million annually (NSW DPI 2012-2013).

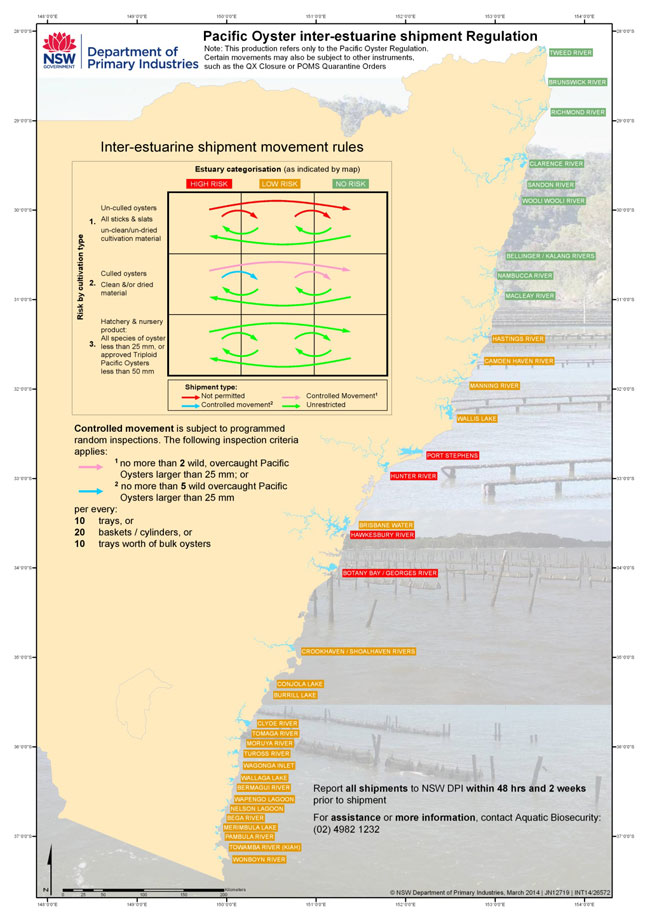

In 2013, the department implemented a new risk-based Pacific Oyster Regulation, which aims to minimise the spread of Pacific Oysters in NSW through movement controls under Division 2A of the Fisheries Management (Aquaculture) Regulation 2012. The Regulation introduces criteria for the movement of oysters and cultivation equipment between NSW estuaries and applies to all Aquaculture Permit holders regarding the cultivation of oysters. This new Regulation was developed using up-to-date Pacific Oyster distribution data and uses a risk based approach. The new regulation has replaced the former Section 8 Fishing Closure (Pacific Oyster) Control. The specifications of the Pacific Oyster Regulation are summarised in the image below.

For more information on the Pacific Oyster Regulation and associated controls, please contact Aquatic Biosecurity.

How can you help?

Like many aquatic pests, once Pacific Oysters are established it is extremely difficult, if not impossible to eradicate them.

Oyster farmers can assist in preventing the further spread of Pacific Oysters by complying with the current rules regarding the movement of oysters between estuaries.

There are several steps you can take to help prevent other marine pests from entering or spreading further in our waterways. For example:

- If you have visited an area known to be infested with a noxious aquatic species, inspect anchors, ropes and chains before leaving the area, and wash your boat and gear down in wash down bays (where provided) or an area away from water bodies and stormwater drains.

- When diving or fishing in NSW waters, keep a lookout for new species.

If you find a new species that you suspect is not native to the area, freeze it whole as soon as possible and Report it!

Further reading

References

Medcof JC, Wolf PH. (1975). Spread of Pacific Oyster worries NSW culturists. Australian Fisheries, 34(7): 32-38.

Pollard DA, Hutchings PA. (1990). A review of exotic marine organisms introduced to the Australian Region: II Invertebrates and Algae. Asia Fisheries Science, 3: 223 - 250.

Thomson JM. (1951). The acclimatisation and growth of the Pacific Oyster (Gryphaea gigas) in Australia. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 3-4: 65-73.

NSW DPI (2013) Aquaculture Production Report 2012-2013. Aquaculture Unit, Port Stephens Fisheries Institute.

Zibrowius M. (1991). Ongoing modification of the Mediterranean marine fauna and flora by the establishment of exotic species. Mesogee, 51:83-107.