QX detection on Port Stephens

QX was detected for the first time in the Port Stephens estuary in August 2021. QX was confirmed through laboratory investigation of oysters sampled from the area after poor oyster growth was observed. A short term control order was put in place under the Biosecurity Act 2015 which placed restrictions on the movement of oysters and oyster cultivation equipment into and out of the estuary whilst the matter was under investigation.

NSW DPI undertook further surveillance in Port Stephens in autumn 2022. The investigation showed that the area met the criteria for a high QX risk area and clause 49 of the Biosecurity Regulation 2017 was updated to reflect the change.

Does QX affect any other species of oyster?

Marteilia sydneyi has only been confirmed to cause disease impacts to the native Sydney Rock Oyster, Saccostrea glomerata. The Sydney rock oyster is the main species of oyster commercially farmed along the east coast of Australia from the NSW/Victorian border north to the Great Sandy Strait in southern Queensland.

Native Flat Oysters (Ostrea angasi) and the introduced Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas; also known by Magallana gigas), also farmed in some estuaries in NSW, are not known to be affected by QX.

How does QX affect oysters?

QX infection in Sydney Rock Oysters is seasonally occurring, usually between January and April, with affected oysters losing condition and dying through autumn and winter. While seasonal, infection dynamics are complex, and it is not always observed each year in those estuaries where it is known to occur.

M. sydneyi has a lifecycle which involves at least two hosts, which means QX cannot be passed directly from one oyster to another (is not directly transmissible). The parasite enters into the soft tissue of Sydney Rock Oyster through its gills and palps (near the oyster's mouth). If it progresses to cause disease, the parasite divides and proliferates. It then migrates to the digestive gland which surrounds the oyster’s stomach and intestine. There it undergoes further development and multiplication to produce spores (sporulation), the end-stage of infection in oysters. Sporulation damages the digestive gland of the oyster, resulting in starvation and eventual death of the oyster.

Time from infection until death can vary between several weeks to several months. Affected oysters can be in poor condition and appear translucent or “watery”. The digestive gland can also appear to be a light tan colour instead of the usual dark brown.

Prior to death of the oyster, the spores are released into the environment where they are taken up by alternate host(s) required in the life cycle of QX. The identity of the alternate host(s) has not been confirmed, but there is evidence suggesting that a polychaete worm (Nephtys australiensis) could play a role in the development of the parasite (Adlard and Nolan, 2015).

What does QX look like?

Individual spores of QX disease are microscopic and cannot be identified without the use of high-power microscopes.

Signs of infection in oysters include:

- lack of growth often seen as an absence of growing lip on the oyster shell,

- loss of condition with oysters appearing abnormally thin and translucent,

- pale digestive glands as spores develop in that tissue.

It should be stressed however that these gross signs are NOT specific to oysters with QX and can be the result of other environmental and nutritional conditions.

Diagnosis of the presence of QX

Diagnosis of QX disease should be undertaken only by laboratories skilled in disease recognition and that have the capacity and certification to undertake diagnostic tests. There are three methods that can be used: histology (microscopic examination of thin tissue sections); cytology (microscopic examination of stained tissue imprints); DNA-based tests (including polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, which tests for evidence of parasite DNA).

The use of these tests is dependent on the stage of infection to be detected and the sensitivity of detection required, both of which have been assessed (FRDC funded projects FRDC2001/630, 2001/214). PCR proved to be the most sensitive, followed by cytology then histology. However, PCR cannot differentiate between the sporulating stages of M. sydneyi and other life stages.

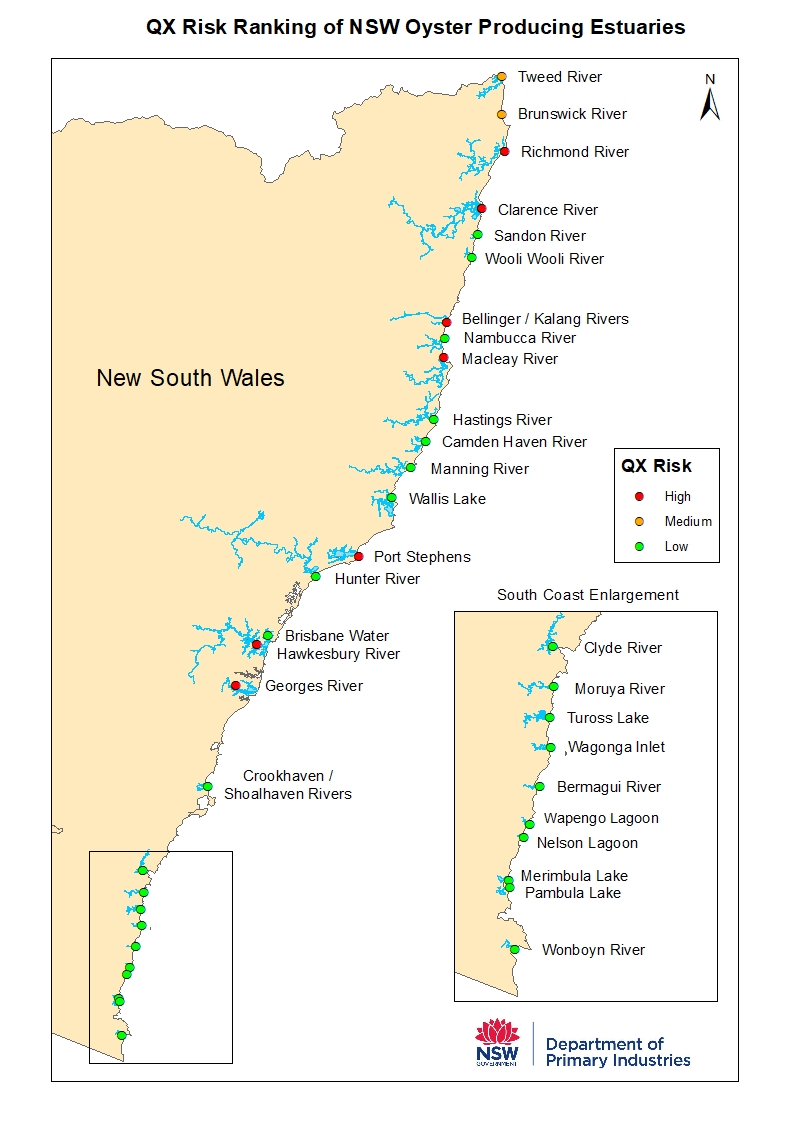

Where does QX occur?

QX historically occurred repeatedly in the estuaries of southeast Queensland and northern New South Wales.

QX historically occurred repeatedly in the estuaries of southeast Queensland and northern New South Wales.

In 1994 it was first diagnosed in the Georges River in Sydney and caused cessation of oyster farming over the following years. A small remnant of the industry returned to the Georges River to farm Sydney Rock Oysters but avoid areas still affected by this disease. In 2004 the Hawkesbury River suffered its first recorded outbreak of QX with massive stock losses, initially mostly on upriver leases, but by 2005 QX caused significant impact on oyster leases downstream too.

A major surveillance program of the east coast growing areas funded by the FRDC and conducted by staff at the Queensland Museum and NSW DPI, was undertaken between 2001 and 2004. As a result of that work, molecular genetic (DNA) evidence suggests M. sydneyi could be far more widespread than previously thought. DNA evidence consistent with M. sydneyi has been found from as far south as the NSW/Victorian border through to northern Moreton Bay in Queensland.

What drives disease outbreaks?

Due to the complex multiple-host lifecycle of the QX parasite in open waterways where oysters are grown there are many factors that can influence development of QX outbreaks.

The short answer is that we don't fully know what drives disease outbreaks, However, major things to consider are:

- Host factors such as the immune response of the oyster

- Parasite factors: such as abundance and availability of the parasite to infect the oyster

- Environmental factors which can affect either the host such as immunosuppression resulting from decreased salinity or temperature affecting development of the parasite.

It is important to note that the presence alone of Marteilia sydneyi does not necessarily result in outbreaks of QX.

What you can do to help

NSW DPI encourages anybody that observes suspected aquatic disease events to report them so they can be investigated. Fish Care Volunteers, recreational fishers and community groups can assist by reporting any observed mortality outbreaks in wild oyster populations.

Cleaning boats, trailers, kayaks fishing gear and other equipment before moving to another waterway can greatly help reduce the spread of aquatic diseases and pests. Read how via this aquatic hygiene factsheet Make 'clean' part of your routine (PDF, 385.23 KB).

The oyster aquaculture industry has an important role to play in managing QX in NSW estuaries. Movement controls are currently in place to manage biosecurity risks posed by shipping cultivated oysters and cultivation equipment between NSW estuaries. See Biosecurity Requirements to read more and ensure you understand your obligations as a NSW aquaculture permit holder.

Resources and further reading

Factsheets and information:

Make 'clean' part of your routine (PDF, 385.23 KB)

Published papers:

Adlard, R.D. & Nolan, M.J. (2015). Elucidating the life cycle of Marteilia sydneyi, the aetiological agent of QX disease in the Sydney rock oyster (Saccostrea glomerata). International Journal for Parasitology, 45:419-426.