Summary of the 2007/08 Equine Influenza Outbreak

Introduction

On 24 August 2007, a veterinarian reported to NSW Department of Primary Industries (NSW DPI) that he had observed sick horses at Centennial Park in Sydney. The report followed an outbreak of equine influenza (EI) in Japan, the import of breeding stallions from Japan into quarantine and reports that some of these stallions at the Eastern Creek Quarantine Station were showing signs of EI.

NSW DPI and Rural Lands Protection Board (RLPB) veterinary staff began an immediate investigation and later the same day, laboratory testing at the NSW DPI veterinary laboratory confirmed that the horses at Centennial Park were infected with EI.

The outbreak that eventuated was the most serious emergency animal disease Australia has experienced in recent history. At its peak, 47,000 horses were infected in NSW on 5943 properties, and horse owners and industry workers were facing dark times with major impacts on their livelihood and lifestyle.

The campaign led by NSW DPI to eradicate the disease was the largest of its type ever undertaken in Australia, using the latest laboratory, vaccine, surveillance, mapping and communication technologies.

The disease was eradicated within six months well ahead of predictions and by July 2008 horse industry operations had returned to normal.

About equine influenza

Equine influenza (EI) is an acute, highly contagious, viral disease which can cause rapidly spreading outbreaks of respiratory disease in horses and other equine species. EI is exotic to Australia and would have a major impact on the Australian horse industry if it were to become established here.

The main clinical signs are usually a sudden increase in temperature (38.5°C or higher); a deep, dry, hacking cough; and a watery nasal discharge, which may later become mucopurulent. Other signs can include depression, loss of appetite, laboured breathing, and muscle pain and stiffness.

Humans do not get infected with equine influenza. However, humans can physically carry the virus on their skin, hair, clothing and shoes, and can therefore transfer the virus to other horses.

Course of the outbreak

Immediately on suspicion of EI infection at Centennial Park, a well planned operation was commenced with the objective of eradicating the disease. A well-trained and prepared first response team was called up and quickly operational, working from the pre-existing Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN).

The NSW Chief Veterinary Officer imposed an immediate state-wide horse movement lockdown on all horse movements and set up a State Disease Control Headquarters at Orange and a Local Disease Control Centre at Menangle. The standstill on horse movements was simultaneously extended across the whole country.

Veterinary investigators launched a major exercise to trace the spread of the disease. Over the next few days the number of properties with infected horses rapidly increased as DPI veterinary investigations revealed new cases throughout the Sydney basin, central coast, northern slopes and north west NSW.

These infections were mainly due to contact with other infected horses before the virus was detected, on 24 August. People unwittingly carrying the virus and airborne spread over short distances also allowed the virus to spread.

Movement and quarantine restrictions initially kept most new infections close to already infected properties, although a few infections caused by prior horse movements soon appeared much further away in new areas such as Parkes, Moonbi, Dubbo and Mudgee.

By the end of August, infection had spread to many parts of Sydney, the NSW Central Coast, and isolated areas in the Hunter Valley. Infection was spreading rapidly in some areas, and there were 18 Restricted Areas, and 488 infected horses on 41 known properties across NSW.

Concentration of horses and adherence to good biosecurity practice were important factors in the rate of spread in particular areas. Infection quickly spread though the Dubbo district for example, where large numbers of horses were in close proximity. However at Mudgee, the horse population was less dense and there was much better adherence to quarantine standards. The spread at Mudgee cleared much more quickly.

Infection continued to spread during the first two weeks of September, but it was increasingly clear that the infection was largely confined to a belt from Sydney, through the Hunter region and into North Western NSW.

From 21 September affected areas were zoned according to the risk of infection:

- 'purple' and 'red' zones were infected areas

- 'amber' zones were buffer areas around infected areas

- 'green' zones were areas that were not infected

As the outbreak progressed, horse movements were carefully managed and only permitted where the risk of transferring disease to another area was very low.

The rate of new infections peaked on 24 September and in late September, vaccination was added to the control strategy to bolster the effectiveness of buffer zones that formed containment lines around the majority of infected areas.

The number of new infected premises recorded each week of the outbreak to the end of December 2007. A 3-week rolling average number of new cases is also shown (red line). The rate of new infections peaked on 24 September, week 5 of this graph.

In early October new infections were confirmed at Barmedman and at Wellington. The distance from other infected properties indicates the virus was transferred on people or equipment to these locations. Strict adherence to mandatory biosecurity precautions would have prevented these new pockets from developing.

The battle waged in the balance in October, but by the end of the month a declining rate of new infections indicated that the NSW DPI control strategy was containing this highly infectious virus. By early November, it was possible to shrink the red zone by 40%.

Progress continued through December, with the last property infected identified on 9 December. On 1 February, interstate movements were freed up, and large parts of NSW were changed to a ‘white zone’ indicating their effective freedom from EI infection.

NSW was finally declared free of EI on 28 February, although horse owners were required to notify all horse movements until the end of June.

It is expected that international requirements for proof-of-freedom will be met by the end of December 2008. Until then all reports of horses with signs consistent with EI are being fully investigated. To date 44 properties have been checked and all have returned negative results.

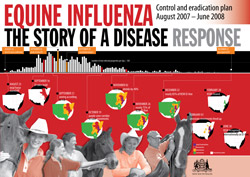

Poster

This poster, 'Equine influenza - the story of a disease response', shows the time frame of the equine influenza control and eradication plan carried out between August 2007 and June 2008.

Download poster, A3 size (PDF, 4.4MB) (web archived)

Was it worth it?

If EI became established in Australia, horse owners would face increased costs for the care and treatment of sick horses and many would face regular vaccination of their horses to enable them to participate in events.

Like human influenza virus, EI virus is prone to mutation and if EI became endemic in the Australian horse population, it is likely that mutation would eventually render current vaccines ineffective, requiring new vaccines to be developed.

Even with an effective vaccine, it is unlikely that enough horses would be vaccinated to protect highly valuable animals such as peak equestrian performers and the racing industry from contact with infected horses.

Countries where EI is present face regular epidemics of the disease when a new strain of the virus emerges. Although EI is common in these countries, these epidemics still disrupt horse events, with the associated loss of income and flow-on effects experienced during the Australian outbreak.

The control strategy implemented in NSW and Queensland during the 2007-08 outbreak of EI contained the outbreak to a relatively limited area of Australia. The impact of the outbreak and control measures on individual horse owners, the horse industry and associated sectors in NSW should not be understated, this impact has to be balanced against the impact of this highly infectious disease on the rest of Australia.

Keys to success

Success in the control of EI was due to a rapid response, based on a thorough and well rehearsed plan (AUSVETPLAN). Cooperation from the horse industry and all associated sectors was also a major contributing factor. Other key factors include the following

- Locking down on all horse movements restricted the spread of EI to a defined area of NSW and Queensland. Cooperation of horse owners in abiding by the lockdown was extremely important.

- Quarantining infected properties and infected areas also helped reduce spread.

- From September, zoning on the basis of risk allowed the lockdown to be eased in areas where there was no EI infection (green zone), while maintaining the restrictions on infected and buffer zones (red and amber zones). Movements were also freed up within the purple zone, where the chance of infection was much higher. This allowed some normal activities, such as breeding, to go ahead.

- Buffer zones, based on geographic features, horse-free areas and strategic vaccination allowed the infection to be held within containment lines.

- New rapid laboratory tests enabled the accurate detection of infected animals using blood tests. It was also possible to distinguish infected from vaccinated horses. Rapid laboratory testing was critical in the initial confirmation of the EI outbreak and in surveillance throughout the control program. Surveillance information provided confidence in what was being observed in the field and reported by the horse-owning public.

Team effort

Over 2000 people were deployed in the NSW control program, working at one of the state and local disease centres, nine forward command posts, 14 local vaccine centres and on affected properties. They included the following personnel:

- Private veterinarians

- Rural Lands Protection Boards

- NSW Police

- Roads & Transport Authority

- State Emergency Service

- Rural Fire Service

- NSW Health.

More than 1500 people from the horse industries worked as part of the EI control operation. Their horse experience or administration skills were well utilised.

- 16,000 movement permits were processed.

- Over 50,000 horses were vaccinated.

- 132,000 laboratory tests were carried out, with as many as 3,000 per day being done at the peak of operations.

- 45 zone progression cases were prepared and submitted for consideration by the national authorities. Each case involved the assembly of a detailed case, supported by comprehensive surveillance.

- 300 media releases were issued, resulting in thousands of radio, television and press interviews.

- 58 public meetings were held, attended by 5,660 people.

- 50 publications were prepared including factsheets, posters and signs. In addition, numerous press advertisements were prepared.

- There were 685,000 unique ‘page views’ generated for the EI home page alone. This does not include views of other web pages, fact sheets and multimedia products available from the EI website.

- Over 62,000 calls were made to the main EI hotline. Many other calls were directed to movements staff, Forward Command Posts and the Local Disease Control Centre.

Published 1 July 2008