Eastern King Prawn project update - June 2014

The project has now completed its first year of research, with the second year now underway before the project's completion date in June 2016. It was started in response to a lack of detailed information about the links between Eastern King Prawns (EKP) and estuarine habitat.

It has been known for some time that EKP spawn out at sea, larvae and juveniles then drift south on the East Australian Current before moving into our coastal estuaries. The tiny prawns spend some months growing in the estuary, before heading out to sea and swimming back up north; where they continue their growth to full maturity and complete the breeding cycle.

However, until now there has been little detail about which parts of the estuary are more important to young EKP. Where do they live? What do they feed on? Are mangroves, seagrass or salt marsh more important; or are they all just as critical? Are some river systems more important than others?

The current project seeks to answer those questions by using a combination of established and innovative research techniques. Juvenile prawns are being caught by our research teams using traditional trawl nets in mangroves, seagrasses and bare sediments across three river systems – the Hunter River, Lake Macquarie and the Clarence River. Then samples of those prawns are tested for their isotopic composition (which measures chemical signatures within the prawn's tissue). These samples can be compared to the signatures of particular habitat types (mangroves, seagrass etc) and let us know where the prawns have been feeding.

Now the first year of research has been completed, some early results are coming to light. This project is a little different in that a big effort is being made to communicate those findings as we go, to the public in general and the commercial EKP fishing industry in particular.

We have used a whole range of different methods, not only to let fishermen know what we are finding; but more importantly to ask them what they would like to know and how would they prefer to get that information.

The project is a three year study that has been funded by the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. Its investment in this exciting body of work is applauded; as is the interest, involvement and support of the commercial EKP fishing industry.

Research

Research summary

- The researchers have completed 400 estuarine trawls across the three study sites (Hunter River, Lake Macquarie and the Clarence River). Just over half of those (230) have been sorted so far;

- Prawns are found in patches in estuarine habitats, not evenly spread across all sites and habitat types;

- Most sites tend to be dominated by just one species of prawn; either Eastern King, School or Greasyback prawns;

- At Hexham Swamp, below the Ironbark Creek floodgates there were more juvenile King and School prawns than at other nearby sites;

- In the Hunter and Clarence rivers, King Prawns tend to be found along the edges of shallow, muddy creeks near mangroves (i.e. near the river mouth);

- School prawns were found in a greater diversity of habitats along the length of the rivers;

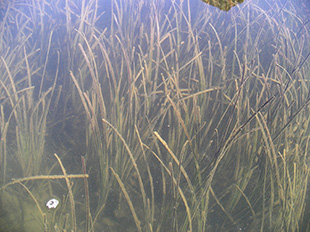

- In Lake Macquarie, King Prawns were found mainly on seagrass beds;

- The chemical isotope method shows promise for separating running / channel prawns on the basis of their nursery habitats;

- Once prawns move offshore and start feeding on marine sources, the ability to track their estuarine origins becomes less viable;

- This coming season, the research program will also look at other prawn species in more detail (particularly School Prawns) and a range of juvenile fish species of recreational and commercial importance.

Detailed Progress Report June 2014

The final phase of rehabilitation of Hexham Swamp (a major rehabilitation program being undertaken in the Hunter River) occurred in October 2013. Opening the final two floodgates restored full tidal connectivity to the swamp through Ironbark Creek for the first time in four decades. Monitoring of the prawns in the rehabilitated habitat included continuing seine net surveys above and below the Ironbark Creek floodgates, and at adjacent reference sites. The lower Ironbark Creek sites, supported greater abundances of juvenile eastern king prawn relative to adjacent reference sites (on Ash Island); however, this impact had yet to extend further up the tributary. Similar trends were found for school prawn.

Over 400 trawls have been conducted across the entire diversity of natural, degraded and rehabilitated habitats in our three study estuaries (the Hunter R., Clarence R., L. Macquarie). Almost 230 of these trawls have been sorted to date, which have yielded almost fifteen thousand prawns; and preliminary exploration of the data is revealing some interesting trends.

As expected, prawns are patchily distributed amongst habitats and sites, and there is an apparent dominance of a single species at most sites - the prawn assemblage is usually dominated by either eastern king prawn, school prawn or greasyback prawn. The first round of sampling indicates that school prawns are by far the most common species, except in Lake Macquarie. In both the Clarence and Hunter Rivers, eastern king prawns were generally concentrated within shallow muddy tidal creeks, in the vicinity of mangrove habitats on the shallow periphery of river channels, and to a lesser extent in seagrass in the Clarence. In Lake Macquarie, eastern king prawns were primarily associated with seagrass, with greasyback prawns in greater abundance within tidal creeks and wetland habitats and school prawns almost completely absent from this system. In general, king prawns were present at densities as high as 5 individuals per square metre (average ≈0.5 individuals per square metre), and were common in many areas that completely lacked any aquatic vegetation.

A key part of the research was to trial stable isotope analysis (which identifies key chemical elements found within prawns to infer their diet and trophic level). Results indicate a good separation of habitats on the basis of isotopic composition, particularly along the estuary gradient. Basically, the isotope approach shows promise for separating migrating (or running) prawns originating from various nursery habitats in the estuaries.

The isotopic signatures of prawns captured from the exploited or emigrating stock at the mouth of the river show different trends for eastern king and school prawns. School prawn isotopic signatures show that at this time point, prawns exiting the system come from a diversity of habitats along the length of river. Eastern king prawns, however, come primarily from mangrove lined, muddy tidal creeks in the lower estuary (i.e. near the mouth). The isotopic composition also indicates that prawns are likely primarily supported in these habitats by benthic microalgal fixation of nitrogen, whereas further up the estuary prawns are supported by enriched nitrogen sources likely coming from agricultural sources through the groundwater. All the general trends reported here will become clearer as sorting of the first season of samples concludes, and isotope analysis of the full sample set is undertaken.

During our preliminary and full-round of sampling in the first season, several commercial species appeared in our catches. These included school prawn (Metapenaeus macleayi), greasyback prawn (Metapenaeus bennettae), and brown tiger prawn (Penaeus esculentus). Various commercial fish species have occasionally appeared in our catch, including bream (Acanthopagrus sp.), luderick (Girella tricuspidata), sea mullet (Mugil cephalus), flathead (Platycephalus fuscus), sand whiting (Sillago ciliata), but almost always in very low numbers (our gear is not overly effective at targeting these species). Following our first round of sampling, it is appropriate to suggest three ways in which we can capitalise on our sampling efforts for eastern king prawn, to provide information regarding other species. Firstly, we intend conduct stable isotope analysis on school prawns in the Hunter River (and possibly the Clarence River, following assessment of our budget at the conclusion of year 2), following the same design specified for king prawns. Secondly, we intend to use density data collected through our sampling to examine habitat associations and potential nursery habitats of other species of penaeid prawns in all our study estuaries, which are appearing in good numbers in some of our samples (e.g. school and greasyback prawns). Finally, our sampling in the second year will focus more on quantitative assessment of abundance. During this round of sampling, we intend to retain and enumerate the fish species described above as they appear in our trawl samples.

Review of scientific literature

There were three elements of Phase 1, which are now completed. The first involved undertaking a desktop review of penaeid use of temperate estuarine habitats, with a species focus on eastern king prawn in NSW. This was necessary to inform sampling design prior to the implementation of the field program, and some relevant notes regarding eastern king prawn that were used to inform the sampling design are summarised here.

Most of the earlier work on estuarine habitat use by eastern king prawn is included in the seminal work of Dakin (1938) and Racek (1959). This work was largely descriptive, but provided a good background to biology and habitat associations in NSW estuaries for both school prawn, eastern king prawn, and to a lesser extent greasyback prawn. Earlier work on eastern king prawn has been done in Moreton Bay (which is more subtropical than temperate) over previous decades. This has revealed some information regarding relative importance of different habitats, particularly seagrass but also highlighting the use of unvegetated habitats by the species, and potential importance of mangroves (Young and Carpenter 1977 and 1978; Skilleter et al., 2005; Halliday, 1995).

Work in NSW has reported association of eastern king prawn with seagrass (Ochwada et al. 2009; Worthington et al. 1995), but has also shown the potential for improved somatic condition in unvegetated habitats as opposed to seagrass habitats (Ochwada et al. 2011). Previous studies in south-east Queensland and NSW (e.g. Dakin, 1938; Racek, 1959) identify that eastern king prawn recruit into estuaries as postlarvae, usually on the nocturnal flood tide (Vance and Pendrey, 2008). There is likely background recruitment occurring to NSW estuaries year-round, but work from Moreton Bay indicates that the largest absolute recruitment may be larger in the late spring (October/November, largest recruitment); with smaller recruitment events in summer (February, smaller recruitment), and late autumn (June, smallest recruitment, Young, 1975). Racek (1959) suggests main recruitment occurs in September and October for NSW estuaries.

Once prawns recruit into NSW estuaries, Racek (1959) proposes that they settle out of the plankton into a "variety" of habitats where they develop as juveniles (usually in salinities >28). They may spend varying amounts of time in the estuarine nursery, with recent anecdotal reports from fishers suggesting 2 months; Racek (1959) suggesting 3-12 months; and Young (1975) suggesting 3 months. Despite this, the departure of eastern king prawn from the estuaries appears to be somewhat synchronized with the lunar phase over the summer months (December to March, Racek, 1959), and occurs primarily on the nocturnal ebb tide between the 6th and 18thday of the lunar phase (although some NSW fishers suggest that runs are more timed with the full moon in rivers, and the new moon in lakes).

Furthermore, eastern king prawn are inclined to run to sea independently of the lunar phase, or at least move down the estuary, following large rainfall events. Anecdotal reports from commercial fishers indicate that once the estuary returns to normal salinity the juvenile prawns may make their way back up to their "nursery" habitats. Following egression from the estuary, eastern king prawn reside in the inner littoral zone (10 to 30 ftm) for a short period as they grow to a largely adolescent stage, before they abruptly move offshore where they migrate, mature and mate.

Previous work on use of estuarine habitats during this period of estuarine residency does not effectively explain the presence of king prawn, sometimes in high numbers, within systems that either completely lack, or have limited submerged aquatic macrophytes. Fishers have repeatedly reported the egression of eastern king prawns from tidal creeks which drain mangrove swamps and saltmarsh, implying that such habitats could be quite important in these systems (certainly preliminary sampling described above supports this). A review of journal articles and grey literature did not turn up many additional studies which reported targeted research on eastern king prawn nursery habitats, and those that reported on habitat associations mostly sampled during the day so should be considered "qualitative". Gibbs et al. (1999; FRDC 95/150) reported large numbers of eastern king prawn in a number of rivers (including the Hunter River) at channel edges in the vicinity of mangrove and saltmarsh habitats.

It is important to point out, however, that most of saltmarsh in NSW is "high marsh" which is infrequently inundated (i.e. only during the highest astronomical tides). Thus, the way in which the marsh itself supports stocks of juvenile penaeid shrimp is likely to be quite different from that of similar penaeid species in the southern United States (which is frequently inundated), where much similar work has been done.

Mapping

A full census of existing data sources for mapping has been undertaken, including archived aerial photography. A time series of aerial photos for all of our study estuaries is available, and some of these have already been digitised and are ready for analysis. When the project moves into the mapping phase, mapping work will be prioritised in the following order: i) Mapping habitat coverage from a "late" set (2000s) and an "early" set (1950s) for each of our study estuaries; ii) Mapping habitat coverage in non-study estuaries (e.g. Macleay River); and iii) Mapping habitat coverage from a "central" (1970s) time point in our study estuaries. The main work for Objective 3 will commence early next year, as per the project timeline.

Communication findings

Information Letters

Following the projects commencement, letters were sent to 18 NSW Fishermen's Cooperatives and the six project partner organisations. The letters provided detail about the project's purpose, objectives, personnel as well as outlining ways for them to get more information and provide further input.

In addition, a further 174 letters were sent to each individual fisher in the EKP fishery. Similarly to the letters described above, these also provided detail about the project's purpose, objectives and personnel; as well as outlining ways for them to get more information and provide input. These letters were accompanied by a hard copy of a fisher survey (described below) and a return stamped envelope for postage back to NSW DPI.

Project Partner Meetings

On the 11thNovember 2013, an inception meeting was hosted by NSW DPI staff at the Newcastle Fishermen's Coop. Invitees included the project partners Hunter Water, Northern Rivers CMA, Hunter Central Rivers CMA, Griffith University, Newcastle Ports Corporation, Origin Energy, PFA, the Newcastle Fishermen's Co-op, and Oceanwatch. This provided an opportunity for project staff to discuss the projects aims, methods and explored ways to more closely engage the partners in the project. A presentation was delivered by Project Leader Dr. Matt Taylor.

On 1stAugust 2014, a second meeting was held at the Newcastle Fishermen's Coop to update the project partners (see above) on the progress and results that had been found to date. Feedback from the partners included support for generating plain English summaries of the results found; in addition to providing more technical detail for relevant audiences such as the Australian Society for Fish Biology. The partners were impressed with the project's progress so far and all look forward to receiving future updates.

Project Updates

The development and release of the project website in December 2013 saw the delivery of the first project update regarding its inception. In addition to this, project updates were made through the inception meeting, radio interviews, newspaper and magazine articles and the use of multiple telephone and face-to-face discussions. The second project update has been prepared following analysis of results collected during the first round of sampling.

EKP Fisher Survey

A survey was designed to elicit desired information from participants in the EKP fishery. It was prepared in tandem with a statistician and fishery managers familiar with the EKP fishery.

The main aims of the survey were to establish:

- the current level of understanding of the role of estuarine habitat in EKP production

- the type of further information that fishers seek on EKP habitat needs

- preferred media for fishers to receive future information

Copies of the survey were sent to each fisher individually (174 sent) along with a stamped return envelope. Interviews have been directly conducted with fishers at several Coops, and further blank copies left at those locations.

So far, 22 surveys have been completed from a total potential of 174, representing a sample size of 12.6%. Some preliminary findings include that:

- The respondents are overwhelmingly male (95.5%) and collectively have 620 years of fishing experience.

- Their average age is 57.

- Geographically, they are distributed from just south of Sydney to the Queensland border.

- They recognise the potential benefits of seagrass, mangroves and wetlands for EKP; less so for saltmarsh.

- Estuarine water quality was seen as of paramount importance to EKP production.

- They believed NSW DPI could do more to restore estuarine productivity by better fixing habitats.

- In terms of information sources that they were confident in, other fishermen were identified as having the necessary hands-on experience.

- When asked about their preferred means of accessing future information, face to-face meetings and addressed letters were the top two responses; however, other methods such as websites, emails, brochures and industry meetings were also popular.

- If a future estuary rehabilitation project was commencing in their area, over 50% of the respondents offered to contribute with hands-on help or providing letters of support.

'Old timer' interviews

Face-to-face discussions with commercial fishers have produced some interesting oral histories and anecdotes, highlighting the historical abundance and use of estuarine swamps by eastern king prawn. Some comments from fishers in relation to Hexham Swamp are outlined below:

Before the floodgates were constructed at Ironbark Creek in the early 1970s, Hexham swamp was considered to be the main nursery of EKP for the Hunter River. The results from tagging studies (which showed prawns migrated north as far afield as off Brisbane) led fishers to conclude that Hexham may have been the main nursery for an even larger area than just the Hunter.

In the 1920s, a local fisherman saw a stream of king prawns 0.5 m wide by 0.5 m deep coming out of Ironbark Creek, out past the Heads and streaming out to sea for 7 - 8 miles towards the north. Then in the 1940s, the local BHP steelworks had ongoing issues with king prawns clogging up the screens on the water intake pipes. Enough prawns would be scraped off to fill a 44 gallon drum. Every two weeks over summer, the cast-off prawn shells would form drift piles on the side of the waterways that would crunch underfoot.

One fisher caught enough prawns in nine days to pay off his new trawler. Another bought a new car with cash, just two weeks after he started prawning. Hexham also provided other resources for locals. The skies were black with ducks and swans. During the Depression in the early 1930s, Hexham supported 200 families that gathered prawns, fish, ducks and other waterfowl for consumption and sale. On Sundays, people hunting ducks with shotguns were so numerous that the booming shotguns made a continuous roar. This went on for years. On seeing an advert promoting tourism to Kakadu, one fisher said "why would you go there? We've got it all here: ducks, magpie geese, jabiru, swans etc - just not the croc's!"

After construction of the floodgates, fishermen noticed a steady decline in their catches of EKP. This decline became increasingly obvious once the swamp really dried out. The numbers of EKP never recovered while the floodgates were in operation. Some fishermen agitated to return water to the swamp and have been engaged since the early 70s to the present day, by sitting on various committees, lobbying politicians and seeking grant funds to actively restore tidal flows.

As a result, the floodgates on Ironbark Creek have been progressively opened during non-flood periods over the last few years. Each year there are increasing numbers of small EKP (<28mm) being seen in Hexham. Landholders living next to the swamp have seen their first Jabiru's in years that were "tossing back beakfuls of juvenile prawns". One fisherman was so confident of a revival of the EKP fishery that he bought a new trawler when he heard that the floodgates were being opened again.

Face to face discussions with commercial fishers

Six Fishermen's Coops have been visited to date (Ballina, Maclean, Coffs Harbour, South West Rocks, Port Macquarie and Newcastle). Coop managers and available fishers were contacted and the project was discussed with them to their satisfaction. Copies of the survey for EKP fishers were also completed wherever possible and interviews conducted. Additional blank copies were left with Coop managers for absent fishers.

In general all fishers received the concept and delivery of the project quite well. In contrast to many of the other issues facing the industry at present, this research was seen to be both important and positive and well geared to assisting the natural enhancement of prawn stocks.

Print media

A media release was prepared and distributed to several media outlets. The information was picked up by several media outlets, which are summarised in the Table below:

Publication | Date | Readership | Source |

Clarence Floodplain Newsletter | December 2013 issue | 750 hard copies plus on Council website | |

DPI Twitter account | 12 Dec 13 | 2,844 followers | |

Newcastle Herald | 19 Dec 13 | 157,000 | |

Northern Star (Lismore) | 20 Dec 13 | 29,000 | |

Professional Fishing Association (PFA) magazine | December 13 issue | 500 hard copies distributed plus website availability |

Radio

An interview on the project's background and inception was conducted by ABC North Coast with Simon Walsh on 16th December 13.

Presentations

The following presentations have been conducted:

- Taylor, MD (2013) The impact of habitat loss and rehabilitation on recruitment to the NSW eastern king prawn fishery. Project Inception Meeting, Newcastle Co-op, 11th November 2013;

- Taylor MD (2013) Habitat – Fishery linkages in New South Wales. Workshop on Agreed Future Directions in Fish Habitat Management in NSW, Royal Botanic Gardens, 22nd August 2013 (attended by ALL major fisheries stakeholder groups in NSW);

- Taylor MD (2013) Challenges and opportunities for fish habitat research: A NSW perspective. Fish Use of Mangroves and Tidal Wetlands: Biological Drivers, Physical Constraints, Regional Variation, Townsville, 1st October 2013;

- Taylor, MD (2014) The impact of habitat loss and rehabilitation on recruitment to the NSW eastern king prawn fishery. Project Partner Update Meeting, Newcastle Co-op, 1st August 2014;

- Russell, K (2014) EKP project extension: Communicating the results. Project Partner Update Meeting, Newcastle Co-op, 1st August 2014.