Citrus in the garden

Series: Agfact H2.1.7 Edition: fifth Last updated: February 2022

Introduction

Apart from the convenience of having fresh fruit readily available, citrus trees make their own contribution to the home garden with their shiny green foliage, pleasant-smelling blossom and attractive fruit colour. Home-grown fresh citrus fruits are nutritious to eat or to juice for healthy and refreshing drinks.

Location

Climate

Citrus are considered subtropical but will grow in most areas of New South Wales, from the coast to the western inland and as far south as the Murray Valley. However, they will generally not grow on the tablelands, where severe frosts can damage the trees and fruit. Provided adequate irrigation is available, trees can tolerate hot conditions, although exposed fruits can be sunburnt.

The cold-hardiness of fruiting citrus types varies significantly. This often influences where certain varieties or types can be grown successfully, as regular frost damage must be avoided. In summary:

- very sensitive: citron, lime and lemon. These usually grow continuously and are susceptible to injury even by very light frosts.

- moderately susceptible: grapefruit, pummelo and sweet oranges.

- cold hardy: Seville, mandarin and Meyer lemon.

- very cold hardy: cumquat.

Rough lemon is a frost-sensitive rootstock and sweet orange moderately susceptible, while citrange is cold-hardy and Poncirus trifoliata very cold-hardy.

Where to establish

Citrus trees grow best in deep (50 cm), well-drained, sandy loam soils. They will not tolerate very acidic or alkaline conditions, preferring a soil pH between 6–7. Maximum sunlight is desirable for fruit growth, setting and maturity. Avoid positions that are low and frost-prone, or exposed to strong winds, particularly sea winds.

If trees are planted in tubs, they will need to be in the sun for at least part of the day to maintain healthy growth. Patios and small courtyards are suitable for tub trees such as Meyer lemons, cumquats and calamondins.

Varieties

Citrus belong to the family Rutaceae, which includes the genera of true citrus fruit, i.e. Citrus, Fortunella, Poncirus, Eremocitrus and Microcitrus.

A wide range of citrus types and varieties is available in Australia, and a good range can usually be planted in any climatically suitable home garden site. By having different varieties growing, fresh citrus can be available over an extended period. However, varieties ripening in summer and autumn are at greater risk of attack by Queensland fruit fly and some fungal diseases.

Oranges (Citrus sinensis)

Washington navel

An early, seedless variety that matures in May and June. Its fruit holds on the tree for several months under favourable conditions. The juice should be used quickly as it becomes bitter, even in short-term storage. In some coastal areas, excessive summer fruit drop or shedding of developing fruit occurs, resulting in very poor navel crops (see the Problems section for more information).

Thomson navel

Matures slightly earlier than Washington. It is also seedless with a fine rind but is not as juicy as the Washington variety.

Leng navel

An early-maturing variety that is very juicy, but the thin rind is prone to splitting. This navel tends to produce small fruit, and excessive preharvest drop can also be a problem. It is suitable for inland areas only.

Lane Late navel

Matures later than the other navels and does not colour until August. It can be very slow to reach satisfactory cropping levels in coastal climates.

Joppa, Parramatta, Homosassa, Siletta, Hamlin and Mediterranean Sweet

All these varieties are mid-season common, seeded oranges that mature in July and August and have good juice content. Trees are easy to grow and cropping is regular, but fruit will only hold on the tree for a short time. All are suitable for home juicing.

Valencia

A late, seeded variety that matures in September and October. Fruit will remain on the tree for 6 months under favourable conditions, but only if it is not damaged by fruit fly or black spot, which can occur in coastal districts. A seedless selection is also available. Valencia is the main growing and juicing variety in the state.

Blood oranges

Three varieties are currently available: Ruby, Maltese and Harvard. Although popular in some Mediterranean countries owing to their distinctive flavour and appearance, they have only a limited appeal in Australia. The amount of rind and flesh pigmentation, particularly under mild coastal growing conditions, is usually disappointing. The hot, dry inland areas are more dependable for pigmentation development.

Lemons (Citrus limon)

Eureka

This variety is suitable for the coastal home garden. It bears several fruit crops: in winter, spring and summer. The tree has few thorns and grows vigorously. Eureka is not compatible with P. trifoliata or citrange rootstocks and is normally propagated on rough lemon or Benton citrange.

Lisbon

A vigorous, thorny variety that is more cold-tolerant than Eureka and more suited to cooler growing areas. The main crop matures in autumn/winter, but light crops ripen in spring in coastal areas. Selected strains are compatible with P. trifoliata and citrange rootstock.

Meyer

A hybrid that is more cold-tolerant than other lemon varieties. The fruit, which is produced throughout the year and is almost orange, has a high juice content and a mild, low-acid flavour.

Lemonade

An Australian seedling originally located in Queensland. A vigorous, heavy-cropping tree with fruit similar to a lemon but with lower acid and a distinctive ‘lemonade’ flavour.

Mandarins (Citrus reticulata)

Several mandarin and related hybrid varieties (tangor and tangelos) are available. Some develop rind colour early, but each variety is mature and retains its fruit quality for a relatively short period (5–6 weeks). Compared with most other citrus types, some varieties are hard to pick and require clipping to reduce rind damage at harvesting. The following popular varieties are listed in their approximate order of maturation, from very early (April) to very late (September).

Satsuma

The Silverhill selection (also known as C. unshiu) is a very early variety and the first to mature (April and May). The tree is very cold-hardy and small. Fruit is seedless, medium-sized, juicy and has bright orange flesh.

Imperial

An early variety that matures in May. The fruit has an excellent flavour but tends to be small when heavy crops are produced. Thinning fruitlets will improve fruit size.

Clementine

The Algerian selection is widely grown in some Mediterranean countries. It is early-maturing, commencing in mid-May. Fruit is well coloured (red–orange), medium to small size, sweet and juicy, but seedy.

Emperor

A mid-season variety that matures between June and August; a late-maturing selection is also available. It has good flavour and is easily peeled. The fruit is subject to brown spot in coastal areas, and the trees tend to overcrop, resulting in smaller fruit size and tree decline.

Thorny

Also a mid-season variety. Fruit is small, sweet and juicy with good flavour, but seedy.

Minneola

A mid-season hybrid, maturing in early July. The fruit has a distinct neck and thin bright reddish-orange rind, which is difficult to peel. Fruit is also subject to brown spot when grown in coastal areas.

Ellendale

Alate variety, maturing in August in the warmer districts but sometimes harvested as late as October in cooler areas. It is not a true mandarin but a natural tangor of good eating quality.

Seminole

An attractive late hybrid mandarin with reddish-orange rind. It is very juicy with a distinctive flavour.

Kara

A good quality, very late maturing variety (end of September).

Grapefruit (Citrus paradisi)

Grapefruit require hot, dry growing conditions to ensure good flavour and quality.

Marsh

A nearly seedless variety with straw-coloured flesh, it can be harvested from July but is sweeter if left until October in the Sydney area. A natural physiological preharvest fruit drop is a common problem and can occur just as the fruit is colouring or before it is fully mature See the Problems section for more details.

Wheeny

A natural hybrid with light, straw-coloured flesh, a distinct lemon flavour and many seeds. It grows vigorously and produces large fruit but has a tendency for alternate cropping.

Pigmented varieties

Of the pink-fleshed varieties, Thompson is similar to Marsh but has a faint red-pink flesh. Ruby and Red Blush have orange-pink flesh and some colour on the skin under favourable hot and dry inland climatic conditions.

Poorman

A hybrid with large, pale orange rind and flesh. This variety is more suitable for growing in colder districts than other true grapefruit varieties.

Chironja

An imported variety that is apparently a natural hybrid of grapefruit and orange. Fruit size and appearance are similar to grapefruit but with an orange flesh that is juicy and sweet, lacking the acid and bitterness of normal grapefruit.

Limes (Citrus aurantifolia)

Limes are only suitable for growing in frost-free sites. They do well in the more tropical areas.

Tahiti (or Persian)

A variety similar in size and shape to a small lemon, but the flesh is seedless and pale green. It should be harvested while the rind is still green, or it can develop stylar end rot and drop from the tree. The juice is not as acidic or aromatic as the Mexican lime, which is preferred for fresh juice drinks. The trees are upright, of medium size and vigour. This variety has good tolerance of tristeza virus disease.

Mexican (or West Indian)

Fruit from this variety is very acidic with a strong lime aroma and flavour, but is smaller than the Tahiti. The trees are also bushier and not as vigorous. They are very likely to decline at a young age from tristeza virus disease, which is spread by black citrus aphids. The tree is also attacked by the melanose fungus.

Sweet limes or sweet lemons (C. limettioides)

These are widely grown in India, where they are considered to have medicinal value. They have an insipid taste because the fruit lacks acidity, and they are not grown commercially. The fruit is medium-sized with a smooth, thin rind, which is greenish to orange–yellow. It has good juice content and few seeds.

Rangpur

An attractive hybrid mandarin–lime variety with orange fruit that is very acidic and suitable only for drinks.

Calamondins (Citrus madurensis)

This fruit has frequently been confused with the round cumquat. Both cumquats and calamondins are attractive ornamental trees and produce distinctive small fruit with many uses.

Although resembling a cumquat, the calamondin is similar to a very small mandarin and has loose, bright orange skin when ripe. The tree blossoms in spring at the same time as mandarin trees, whereas cumquats flower in early summer. Variegated calamondin leaves and fruit are shown at right.

The calamondin has been used mainly as an ornamental tree in the garden or in a tub, but the fruit, although it lacks sweet flesh and skin taste, can be made into a tasty marmalade.

.

Cumquats (Fortunella spp.)

Cumquats belong to a citrus subspecies. The oval cumquat (Nagami, shown at right) is available from nurseries and can be easily identified by the oval shape of the fruit. It makes an attractive ornamental tree in the garden or in a tub. The fruit has a sweet, oily skin and can be eaten whole, crystallised, or used to make jams, conserves and liqueurs. The main blossoming does not occur until after November, but the crop matures unevenly and fruit is on the tree for long periods.

The round cumquat resembles Nagami but is more rounded and has more segments and a sweeter flesh and rind flavour. The round cumquat available in the Sydney area is thought to be the Meiwa selection. As with the oval cumquat, blossoming is delayed until after November because of the tree’s dormant habit, and this makes it particularly well suited to colder climates with late frosts.

A variegated (light green and pale yellow) foliaged cumquat selection is also available.

Other citrus varieties

Chinotto (Citrus myrtifolia)

Fruit from this variety is bitter and not pleasant to eat fresh but is sometimes used for candying or crystallising. The tree has unusually shiny small leaves on thornless branches, and with its large, orange fruit, it makes an attractive tub specimen.

Seville (Citrus aurantium)

This variety has a very bitter, orange fruit known as ‘sour orange’. It is used commercially for marmalade. Both smooth-skinned and rough-skinned selections are available.

Pummelo (Citrus maxima)

Indigenous to the Malayan peninsula, this variety was carried to other countries by traders. It is also known as a ‘shaddock’. It has very large, yellow-green fruit with coarse pink or white flesh and a very thick white rind, which makes it suitable for marmalade. It can be used as a substitute for grapefruit. The local selections are highly variable and have little use in the home garden, except for the novelty value of the very large fruit.

Citron (Citrus medical)

This is one of the oldest citrus species known and grown. It has special religious significance. The fruit is large, oblong, thick-skinned and very aromatic, but it is bitter and virtually non-edible; however, it can be used for marmalade or the peel can be candied. The tree is small, weak-growing and short-lived because it is very sensitive to wind, frost, heat and the common tristeza (‘quick decline’) virus disease.

Kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix) This variety is an exotic type with an unusually large-winged petiole leaf that is dried and used widely as a seasoning in cooking, particularly in South-East Asia. The fruit is very bumpy, full of seed and with very little juice.

Propagation

Citrus trees grown from seed are normally very variable and do not produce true-to-type trees or fruits. Common varieties, available from local nurseries, are normally propagated by budding the required scion or variety onto specially grown and suitable rootstocks (understocks).

The most commonly used rootstocks for citrus are P. trifoliata and rough lemon, but Troyer, Carrizo and Benton citrange, Cleopatra and Emperor mandarin, and sweet orange are also used to propagate trees in some localities. Different rootstocks will adapt citrus to various soil conditions, such as light (sandy), heavy (clay), alkaline, saline, or soil containing citrus nematodes.

P. trifoliata and the citrange rootstocks have resistance to phytophthora root rot and are used in heavier soil types where drainage problems are expected or where trees are planted to replace others that have been removed. They can be used for all varieties except Eureka lemon. Benton citrange, however, can be used for this variety.

Rough lemon is very susceptible to phytophthora root rot but is suitable for all varieties except Ellendale and Imperial mandarins.

Planting

Citrus nursery trees are normally sold in containers, although some may be available as bare-rooted trees. Prepare the site by digging over several months before planting. Add organic matter and remove troublesome weeds.

The best time for planting a citrus tree is when the risk of severe frost is past, usually in August or September. Advanced trees that have been grown in containers can be planted during spring, summer or early autumn provided there is little disturbance to the main root system and they are watered frequently. Where summers are hot and dry and winters are mild, trees can also be planted in autumn.

When planting any citrus tree, prepare the site well beforehand. Dig the planting hole deep enough to allow the tree to be placed at the original nursery or container soil level, with the bud union at least 15 cm above the ground level, and wide enough for the roots to spread out. Remove the tree from the container and gently tease the external roots to free them for planting (or for removal if they have spiralled in the container).

Do not put artificial fertilisers in the planting hole. If the tree is planted too deep or allowed to settle below ground level, the value of the rootstock will be lost. Make sure the soil is pressed firmly around the tree’s base and form a basin around the tree to make watering easier. Pour about 10 L of water slowly into the basin to consolidate the tree and provide a reserve of moisture. Water several times a week until new shoots appear.

Tree care

In the first year of growth, water the tree every 4–7 days, depending on the weather. Regular watering is essential during hot, dry, windy periods.

When the tree is well established, watering can be limited to a good soaking with a sprinkler every week. Tub-planted trees will need to be watered more frequently, depending on the amount of soil and the growing position.

Citrus tree root systems are usually concentrated in the top 30 cm of soil and within the ‘drip ring’. If a mulch has formed or is maintained under the canopy, many of the important fibre roots will be found within 10 cm of the surface. Take care when digging around the tree not to damage larger roots, as an injury might result in invasion by wood-rotting phytophthora fungi. Heaping grass clippings or other material around the base or trunk of the tree can result in similar problems.

Remove weeds by light chipping or mowing until the canopy develops and reduces light under the tree, thus inhibiting weed growth. Problem weeds such as couch, kikuyu or summer grass can also be controlled by the careful use of registered herbicides. Some that are safe to apply near citrus can be injurious to other nearby fruit trees, shrubs or plants in the garden. Refer to the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) for more detailed information.

Trees planted in tubs might require repotting into larger containers after several years, or root pruning if the tree is to be kept small. Artificial fertilisers might damage the roots and burn the foliage, so it is safer to use blood and bone or slow-release, mixed fertilisers (pellets or tablets) for these trees. See the Nutrition section for more information.

Pruning

Foliage might benefit from light pruning at planting if the root system has been badly damaged or reduced to fit in a tub. If the tree was grown in a shallow container, it might be necessary to cut the tap root to remove spiralled growth before planting.

Apart from removing suckers and shoots from the rootstock and trunk, there is no need to prune the tree until the dead wood has to be removed. The citrus tree is self-shaping but in time the shaded inside twigs and limbs should be removed to open the centre and reduce the risk of fungal diseases such as melanose.

Pruning hints

- Cut out all dead or diseased wood cleanly; do not leave stubs.

- Remove crowded or crossed-over branches.

- Paint cuts that are larger than 2 cm across with a bituminous-type wound dressing.

- Prune in the spring when the danger of frosts is over.

The lower growth (up to 30 cm above ground level) can also be removed if necessary to assist in the tree’s soil management. This pruning is called ‘skirting’.

If individual branches impede access or are crowding other trees, fences or paths, they can be removed completely or cut back to any convenient position. Citrus trees readily produce new growth from near major pruning cuts.

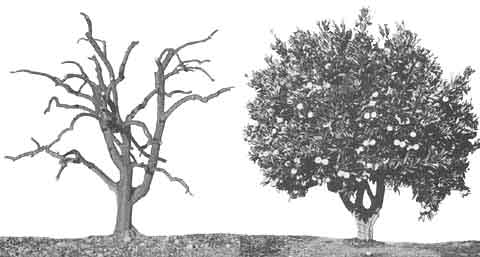

Orange and lemon trees that have lost vigour but have a sound root system and trunk might be rejuvenated by a skeleton pruning, that is, a severe cutting back in spring. This can rejuvenate some citrus trees into completely new growth. Remove all the leaves and twigs cleanly and cut all the main branches that form the framework at 2–3 cm diameter so that only the tree’s skeleton remains. Seal the main cuts as described earlier and whitewash the limbs and trunk to protect against sunburn.

Skeleton pruning (on the left) can rejuvenate some citrus trees into completely new growth.

The tree on the right shows the result of having been skeleton pruned 2 years earlier.

Nutrition

Most garden soils require some annual fertilisers for good tree development, fruit size and regular cropping. Citrus trees, being evergreen, have two main growth flushes (spring and autumn) and therefore require more than most deciduous trees or vines.

The main nutrition requirement is nitrogen to promote growth and fruit size. Phosphorus is also usually lacking, and, if the soil is a light sand, regular additions of potassium are needed to maintain tree health and fruit quality. Magnesium and calcium might be needed in some soils, together with small amounts of the trace elements zinc, manganese and copper.

For more detailed information, see Citrus nutrition.

Type and amount of fertiliser

The main fertiliser needs of citrus trees can be applied as organic/animal manures or artificial/chemical fertilisers.

For non-bearing trees, organic manures can be convenient and supply adequate plant elements and organic matter to the soil. Provided these manures are not too fresh, they can be applied safely to young trees in autumn or winter. As a guide, apply 4–8 kg for 1-year-old trees, increasing annually up to 16–32 kg by the eighth year.

As bearing trees would require large amounts of organic manures (20–40 kg per tree), they are instead usually given a complete ready-mixed citrus fertiliser such as 10:4:6 or 10:3:6* at the rate of 500 g per year of tree age until the tree is 10 years old, then at the rate of 5 kg per year applied in the later winter. Give high-producing trees a supplementary application of nitrogen (700 g ammonium sulfate) in November.

*These ratios represent the proportions in which the constituent elements are present in artificial fertilisers:

nitrogen : phosphorus : potassium (N:P:K)

Mixed fertilisers can also be used for non-bearing trees, at the above rate. When used for non-bearing trees, three-fifths of the annual amount can be applied in late winter and two-fifths in summer. For very light soils a ‘little and often’ program in the growing period can be followed, particularly for non-bearing trees.

Applying fertiliser

Most citrus trees blossom once a year in the spring, and the applied nitrogen should be available at that time.

Whatever type of fertiliser is used, spread the required amount evenly around the tree, avoiding the trunk, and water after each application. This spreading should be 0.5–1 m wide for young trees, and to the drip ring or foliage edge for bearing trees.

Correcting low soil pH to 6–7.5 with dolomite, magnesite or agricultural lime will improve tree health generally and ensure that other fertilisers applied become available to the tree.

Deficiencies of nitrogen, magnesium, zinc and manganese are fairly common in citrus trees and can normally be corrected easily, but the correct identification of any nutrient deficiency is important. See the section on Common nutrient disorders.

Harvesting

For all varieties except limes, fruit should be left on the tree until they have developed full colour and flavour. Unlike many other fruits, mature citrus can be held on the tree for some time, but quality will eventually deteriorate and pest and disease problems might increase losses.

Citrus fruit should be handled carefully and picked with a twisting–pulling action that breaks the stalk but does not damage the button or the fruit. Do not pick cold or wet fruit, as shelf life can be severely reduced.

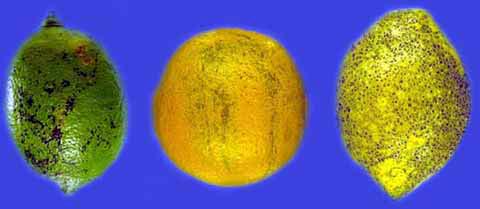

Surplus fruit can be stored for several weeks in the crisper of the refrigerator. Lemons can also be cured and stored for long periods:

- clip dry fruit at first colour change from dark green to light green (silver)

- handle carefully

- store in paper-lined or dry sand-filled boxes in a cool, dark place away from draughts but with good ventilation.

Problems

Summer fruit drop

Citrus normally shed large numbers of fruitlets shortly after blossoming in spring and at early fruit set (pea size). However, it is also common for a sudden drop of small fruit (20 mm diameter) to happen in summer, when warmer weather stresses the tree. The problem is particularly severe in young navel orange trees and can be related to lack of water at, or soon after, fruit set. Root diseases and lack of nitrogen or trace elements might also be responsible.

Rind splitting

Rind splitting, particularly in navels, also occurs before or near maturity as a result of climatic factors, specifically a drop in average temperatures and an increase in relative humidity when the rate of fruit growth is decreasing. There is no control for the disorder.

Preharvest drop

Preharvest drop in autumn before fruit is fully mature is a common problem with navels and grapefruit. Some of this drop is natural, but in coastal areas, fruit stung by Queensland fruit fly during the late autumn colour change period is also very prone to drop. Some mandarin and lemon varieties will also shed fruit when damaged by the spined citrus bug. Brown spot infection in mandarins will result in fruit drop.

Alternate cropping (biennial bearing)

Alternate cropping (biennial bearing) is a common problem with many citrus varieties, such as Valencia orange, Wheeny grapefruit and mandarins. After a heavy crop, the tree often responds by carrying a light (or nil) crop. Once this cropping pattern is established it is difficult to return to regular annual cropping. Pruning or thinning of the heavy crop and early harvesting will assist in reducing the problem.

Second crop fruit

Sometimes orange trees will produce blossoms in the autumn after a stress period and set a second crop. This fruit is often of poor quality (thick skins and low juice content) and is susceptible to fruit fly attack. With lemon trees, however, these intermediate crops are desirable.

Pests, diseases and nutrient disorders

Warning

Pesticide residues can occur in animals treated with pesticides, or fed any crop product, including crop waste, that has been sprayed with pesticides.

It is the responsibility of the person applying a pesticide to do all things necessary to avoid spray drift onto adjoining land or waterways.

Always read the label

Users of agricultural (or veterinary) chemical products must always read the label and any Permit before using the product, and strictly comply with the directions on the label and the conditions of any Permit. Users are not absolved from compliance with the directions on the label or the conditions of the Permit by reason of any statement made or not made in this publication. Refer to the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) for more detailed information.

A wide range of pests and diseases can affect both the fruit and the tree. Citrus can also suffer several nutrient disorders. Most of these problems can be resolved by spraying with registered and recommended pesticides.

Identify insect pests correctly and do not spray unnecessarily. Small numbers of pests might not cause any significant damage or crop losses in the home garden. Some can be picked off the tree and destroyed without the need for any spraying. Many pesticides are also toxic to bees and other beneficial insects that provide natural control of some pests on citrus trees.

With most diseases, infection takes place before visual symptoms appear, so routine protective sprays are normally needed. In coastal districts, diseases can be more common and damaging owing to the more favourable (wetter and more humid) seasonal conditions. In the drier and hotter inland areas, fewer citrus disease problems occur.

Nutrient disorders are corrected by fertiliser or trace element applications, but these can be harmful if used incorrectly or unnecessarily.

See also Citrus pests, diseases and disorders.

Common pests

Scale insects, Queensland fruit fly, bronze orange bug, spined citrus bug, mites, citrus leaf miner, aphids and citrus butterfly caterpillars are common pests of citrus.

There are several types of scale insect:

- White wax scale and black scale mainly affect the tree by producing honeydew, on which sooty mould develops.

- Citrus red scale blemishes fruit and can harm tree health.

- White louse scale, which is mainly on the trunk and larger limbs, can also seriously impair tree health.

|  |

(L - R) White wax and black scale

|  |

(L - R) Red and White louse scale

Queensland fruit fly are common in coastal districts and the central and northern inland districts of New South Wales. It can attack citrus from September to May, depending on the fruit variety. Cover-spray treatments reduce fruit losses. Do not leave fruit on the tree beyond full maturity.

In coastal districts and the central west and north-western districts, watch for bronze orange bug and spined citrus bug, which reduce fruit production. Bronze orange bug is a native pest of coastal citrus. In spring and summer, the bugs suck sap from young shoots, leaves and flowers, or fruit stalks, causing them to fall.

|  |

(L - R) Bronze orange bug, Spined citrus bug

New growth can be damaged by the citrus leaf miner in coastal districts, and black citrus aphid and the caterpillar of the citrus butterfly (Museum Victoria images) in all areas (the citrus butterfly is also known as the ‘small citrus butterfly’ or the ‘dingy swallowtail butterfly’).

|  |

(L - R) Citrus leaf miner, Black citrus aphid

Common diseases

Melanose, citrus scab, black spot, brown spot and brown rot are common coastal fungal diseases that can be reduced by spraying with recommended fungicides. Fungal spores can live on dead twigs and wood. As trees age, the amount of dead wood increases as does the level of disease. To reduce disease problems, keep your trees clean by pruning out dead twigs and wood annually.

Melanose occurs in coastal areas and produces dark brown spots (or tear stains) on the fruit, leaves and twigs. Infection is reduced by spraying with protectant copper fungicides after petals fall.

Citrus scab occurs in coastal areas and appears as scabby areas mainly on lemon fruit and leaves. Infection is reduced by spraying with recommended fungicides at half petal fall.

Black spot occurs in coastal areas and appears as dark spots on mature citrus, particularly Valencia oranges. Infection is largely prevented by spraying with recommended fungicides at petal fall. A second spray is required 16 weeks later. Harvesting fruit early in the season reduces black spot problems.

Brown spot fungus disease affects mainly mandarins, especially the Emperor and Minneola varieties. Both leaves and fruit can be infected, particularly in cool damp weather during early spring to early autumn. Up to 4 sprays might be necessary to control heavy infections under favourable conditions.

Brown rot occurs on fruit, usually under wet, humid conditions, and is prevented with a protectant fungicide spray applied in March or April. This is also useful in preventing sooty blotch and sooty mould.

Trunk or collar rot and root rots caused by Phytophthora citrophthora occur in poorly drained soils and can cause tree decline or death. The first symptom of trunk or collar rot is death of a section of bark on the trunk near ground level. This is often accompanied by production of gum and cracking as the dead bark dries out. Trunk rots, if not too extensive, can be treated by removing affected bark and then painting with a recommended fungicide paste. Lemons are very susceptible to this disease and tree losses are common.

|  |

(L - R) Brown rot, Collar rot

Common nutrient disorders

Nutrient disorders are generally from deficiencies of nitrogen, magnesium, manganese or zinc.

Nitrogen is the most important nutrient for citrus, and for most soils it is needed as the major component in fertiliser applied regularly around the tree. Nitrogen-deficient trees are recognised by small, uniformly pale leaves; they are thinly foliaged and stunted, with reduced flowering and fruit set.

Orange tree leaves showing increasing paleness due to nitrogen deficiency. Left to right: normal healthy leaf, leaf slightly deficient in nitrogen, and leaf very deficient in nitrogen. The loss of green colour occurs evenly over the leaf. |  Nitrogen deficiency dramatically affects tree growth and production. Leaves deficient in nitrogen are pale, narrow, upright and slightly rolled; foliage is thin due to leaf fall, and twigs die back, giving the tree a brushy appearance. |  Vein clearing in the leaves of an orange tree is usually associated with root injury or girdling but can occur when normally well-fertilised trees are suddenly deprived of nitrogen. |

Magnesium deficiency (occurring most commonly in coastal districts), zinc deficiency (occurring most severely in inland districts), and manganese deficiency (occurring in both coastal and inland areas) can all adversely affect tree growth and cropping. They can be recognised by distinctive colour patterns in the foliage.

Magnesium deficiency in orange trees results in a distinct yellow pattern in the older leaves. The yellowing begins near the edge and towards the apex, leaving a triangle of green at the base of the leaf. |  Magnesium deficiency in lemon trees also results in a distinct yellow pattern in the older leaves. The yellowing begins near the edge and towards the apex, leaving a triangle of green at the base of the leaf. |  Magnesium deficiency affects the older leaves first, note the young leaves are showing no pattern. A heavy crop can accentuate the deficiency in late summer, leading to a heavy fall of the yellow leaves in autumn. The tree can be left severely defoliated and weakened. |

Zinc deficiency produces a bright creamy-yellow mottle. Leaves remain small and narrow (‘little leaf’) and stems are short, giving growth a bunched appearance. Symptoms are usually worse on the northern (sunny) side of the tree. |  Zinc deficiency is usually most severe in spring growth. Note that leaves from the previous summer flush are not affected. |  When the deficiency is severe and is not treated, both the summer flush leaves and the spring flush leaves are affected. |

| Manganese deficiency causes a diffuse pale green mottle between the veins in young and old leaves. The leaf size is normal. A narrow band remains green on each side of major veins. Symptoms are more noticeable on the southern side of the tree. Spring growth is affected, and both young and mature leaves can show the symptoms. |

For further information, see Citrus nutrition.