Improving fish habitats

The NSW DPI is at the forefront of aquatic habitat repair. NSW DPI plays a lead role in rehabilitating fish habitat and native fish populations in NSW through the Aquatic Habitat Rehabilitation Program (AHR Program) and the formation of strategic partnerships.

Key ways to improve fish habitat are to

- restore instream woody habitat ("re-snagging")

- restore riparian areas by removing , replanting with native plants and fencing

- improve fish passage by installing fishways, making road crossings more fish friendly, removing weirs and actively managing floodgates.

Re-snagging

Snag myths

Millions of snags have been removed from Australian rivers in the past. They were previously thought to;

- reduce the capacity of rivers during flooding

- increase erosion

- hinder the navigation of watercraft

- reduce the efficiency of water delivery

- threaten safe swimming

- reduce aesthetics – snags were thought to be "messy".

Many of these impacts have been overstated or proven incorrect. We now know that snags:

- do not significantly decrease channel capacity or lead to increased flooding

- are a natural part of erosion and deposition processes

- are a natural part of rivers and the aquatic environment has adapated to their presence over time.

Reinstating woody habitats

The distribution of natural woody habitat in riverine environments is dependent on the topography and hydrology of the riverine system. The placement of woody habitats into a river is a time consuming and potentially dangerous process which has to take into account practical and social, economic and environmental issues relevant to each particular site. A detailed site assessment is recommended and permits/approvals are often required.

Where possible, woody habitat needs to be placed in congregations or piles and evenly distributed throughout a defined reach. This ensures suitable types of woody habitats are reinstated and suitable connectivity is established between areas of fish habitat.

Each potential snag must be assessed for suitability and can be modified if required. Each snag requires careful placement, with the shape and attributes of the snag suited to the characteristics of site in the river (other vegetation, bank, water flow and direction and so on).

Case Study - Hume to Yarrawonga Resnagging

The following reports cover examples of risk management issues you should consider when undertaking a resnagging project. The risks highlighted in these examples are indicative only, and consultation should be undertaken with relevant authorities early during project development.

- Hume to Yarrawonga Resnagging and Riparian Restoration Feasibility Study FINAL 2005

- Hume to Yarrawonga Risk Management Plan FINAL 2006

Case Study - Assessing snags in the Lachlan

Snags are a natural and common feature of the Lachlan River channel around Hillston. However, snags have a chequered history in terms of how we use and value the river. So are snags obstacles to be removed or vital elements of a healthy ecosystem? The answer is both. The challenge is to manage snags for the benefit of all river users.

The Local Land Services and NSW DPI, in consultation with landholders, have prepared the Lower Lachlan Snag Management Plan. The Plan provides guidance for the sustainable management of snags in the Lachlan River between Redbank Corner and Booligal.

The Snag Management Plan is based on detailed assessment of the current state of the Lachlan River's habitat in 10km reaches of the river. There are now 29 maps showing the location of individual snags or log jams in the 290km of river between Redbank Corner and Booligal.

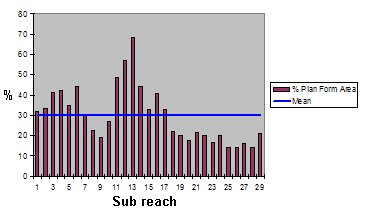

By comparing the total area of snags to the total reach area we understand more about the suitability of the reach and the sub-reaches as fish habitat (see Figure below).

The Redbank Corner to Booligal reach has a generally amount of woody habitat compared to other lowland rivers in NSW. However, there is some significant variation in the number and density of snags in the sub reaches. Thirteen reaches could sustain some woody habitat management or removal. However, appropriate offsets are needed: for example, the relocation of snags into reaches that have a relatively little woody habitat. This will mean that more of the river is better suited to our native fish.

Finding materials to use

Habitats can be constructed out of woody material sourced from development activities (for example, subdivisions that involve clearing vegetation and road and bridge construction), redundant bridges or other infrastructure to imitate the roughness and structure of natural woody habitats. Instream erosion control structure, such as timber groynes and other bed-control devices, can be extended to include submerged complexes that can act as a surrogate to natural woody habitats.

Additional woody habitats can also be sourced opportunistically, for example timber washed up to weirs and bridges during floods.

The effect of resnagging on waterway users

The effects of resnagging on waterway users can be minimised by identifying priority resnagging areas away from the most popular boating areas. Woody habitats can also be secured safely and positioned in a way that does not block the river channel.

River restoration activities will not adversely impact on recreational fishing. Resnagging aims to enhance native fish habitat, thereby leading to a more robust fish community resulting in benefits for recreational fishers.

Restoring riparian vegetation

The vegetation within the riparian area is important. There are several activities required to rehabilitate riparian vegetation, including:

- weed removal

- replanting with appropriate, native plants

- fencing to exclude or manage stock access.

Weed removal

Weeds can out-compete native vegetation, substantially changing the composition of riparian lands. This is undesirable as the weeds may not support native animals, can harbour feral animals, and have different life cycles to native vegetation. For example, a single large leaf drop once a year (such as occurs with willow) does not provide habitat for native animals and changes water quality in ways that suit introduced species, like carp.

Bare and disturbed soils are often the sites where weeds establish. A healthy, dense riparian area will often out-compete weeds and prevent them from establishing.

Aquatic weeds are of particular concern choking streams so that fish passage is prevented, reducing channel capacity and leading to problems of increased flooding, and producing high levels of biomass that create anoxic conditions. For example, para grass, an exotic species that grows in tropical agricultural streams can reduce channel capacity by 20 times, create anoxic waters and decrease aquatic biodiversity to a fraction of natural levels.

Many weeds are identified as noxious in State legislation. Some weeds are listed as "weeds of national significance". Such species must be removed and destroyed.

Replanting

NSW DPI is working with landholders, communities and Local Land Services to rehabilitate riparian vegetation. Important considerations include:

- what species should be planted for the landscape

- site preparation, including attention to weed control and soil moisture

- site maintenance – how the revegetation will be protected from damage competition, weed invasion, fire risk, stock and so on.

Stock access is a major issue when rehabilitating vegetation in riparian areas. It is important to assess the existing vegetation to see if planting is actually necessary. It may be more effective, and certainly cheaper, to encourage natural regeneration once livestock access has been controlled.

Fencing riparian zones

Fencing waterways and controlling stock access is often regarded as the first stage to improving the waterway. Fencing will promote:

- improved aquatic habitat for fish and other species

- improved water quality through reduced input of faecal nutrients and sediments

- bank stability by preventing slumping and erosion

- reduced stock loss from bogging and drowning

- improved aesthetic qualities of the farm.

See also ...

- Aquatic Habitat Rehabilitation Grants Program

- Fixing freshwater fish habitat: a report on 10 projects funded by the NSW Recreational Fishing Freshwater Trust Fund

- A report on planting seagrass