NSW’s Chief Veterinary Officer issued a May 2022 bulletin which reported 26 horses with probable JE and four horses as possible cases. No horses have been definitively confirmed with JE, but clinical signs and test results suggested probable or possible JE infection.

JE is not a food safety concern. Commercially produced pork meat or pork products are safe to consume.

Why is JE a concern?

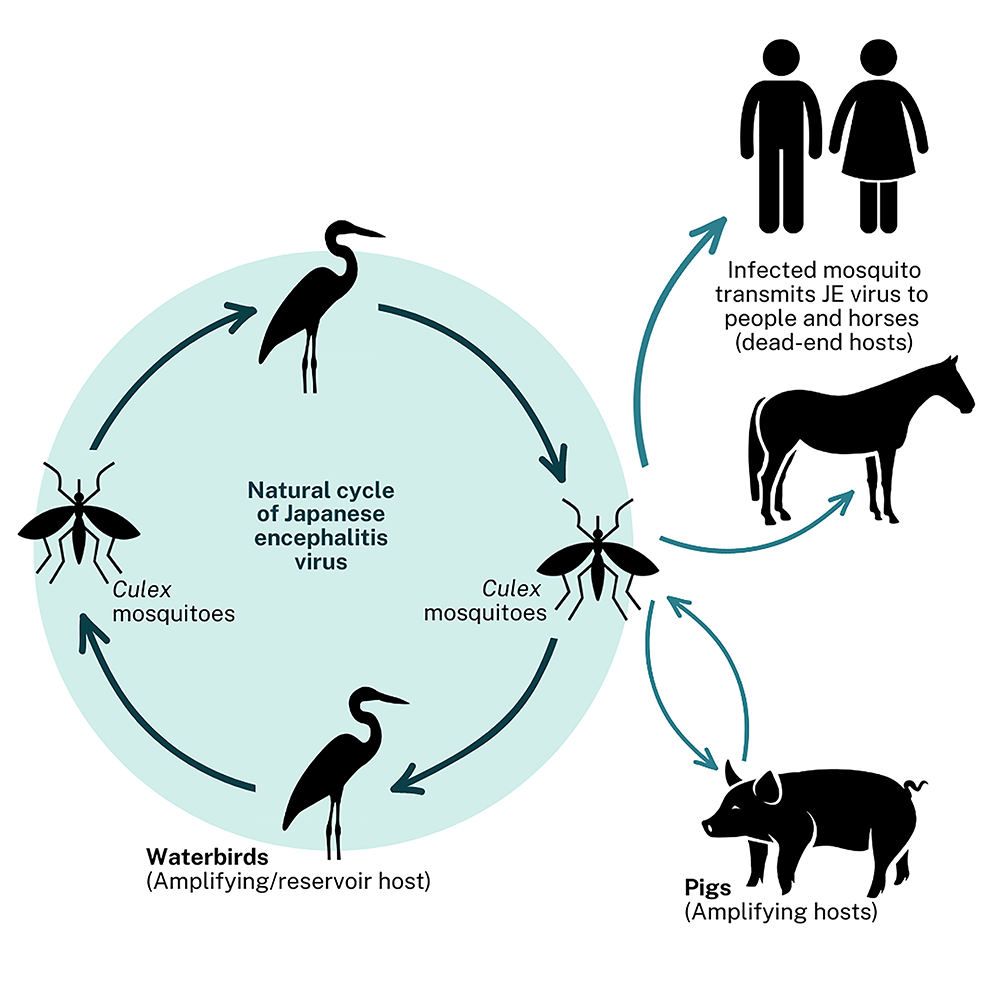

JE is an acute mosquito-borne viral disease that can cause reproductive losses and encephalitis in susceptible species. The disease occurs mostly in pigs and horses and can rarely cause disease in people. Animals and people become infected through the bite of infected mosquitoes. Other species can be infected but do not always exhibit disease including, horses, cattle, dogs, sheep, alpacas and goats which are dead-end hosts, which do not pass the virus on.

The normal JE lifecycle is between waterbirds and mosquitos, which may transfer to pigs and horses.

Current NSW situation

All infected properties have been resolved in NSW. The NSW JE control order expired on 17 June 2022 and now JE is an ongoing NSW DPI animal biosecurity management program, in conjunction with NSW Health and the national strategy, which includes surveillance and management of the disease in animals and people.

JE is a nationally notifiable disease and is classified as prohibited matter under the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015. Producers and animal owners should immediately report any unusual signs of disease or death in pigs, horses or other livestock to the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline, 1800 675 88.

How do producers manage JE?

National policy is to control JE in domestic animals to support public health agencies and industries. Management strategies include:

- Early recognition and laboratory confirmation of cases

- Coordination and cooperation with public health response activities

- Ongoing mosquito monitoring, management and control in high-risk areas

- Risk assessment of JE cases and development of management plans to minimise the risk of spread.

NSW DPI and LLS work with NSW Health and national agencies in delivering mosquito and JE surveillance programs, proactive planning and preparedness.

Currently, Australia has no effective treatment for JE in animals. The best way to protect animals is by developing and implementing an integrated mosquito management plan, which targets all stages of the mosquito life cycle to break the breeding cycle. Vaccination is recommended for people in high-risk groups.

Cooler months present an opportunity to review production and land management practices, develop a mosquito management plan for your property and farming situation and prepare for the next mosquito season.