- GVP $501 million est. Up 1.7% year-on-year.

- Production of chickpeas expected to be 11% lower in 2021-22 year-on-year.

- Faba bean exports increased 23% year-on-year to 55,192 tonnes.

Production

Price

Trade

Value of pulse exports by major destination 35

- Bangladesh

- Egypt

- Pakistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Nepal

- Other

Sustained high freight rates and container shortages has encouraged an increased number of bulk shipments of pulses which have typically been containerised, a trend that has continued over the last couple of years. 237 Industry reports highlighted that freight costs for chickpeas to Pakistan for example had increased substantially with freight representing approximately half the costs of landed chickpeas. By contrast, freight represented 20-30% of landed costs in 2019. 243

Macroeconomic Conditions

North American supplies of pulses continue to be impacted by the dry seasonal conditions experienced in 2020-2021, with low stocks from Canada, the largest pulse crop exporter, supporting prices. 240 Although in the case of chickpeas, Canadian kabuli chickpeas provide limited competition with Australian desi production. 233

Pulse export markets were volatile, with exports tending to be concentrated on a few major markets, particularly South Asian and Middle Eastern destinations. Food inflation globally including amongst the key markets for pulses in South Asia, was of concern. 236 Bangladesh and Pakistan, who represent the major destination for chickpea exports, are facing substantially devalued currencies leading to increased domestic prices. Logistic and inflationary issues are also impacting Pakistani demand. 239

Through 2021-22, India relaxed tariff levels on selected pulse crops for example, the Indian government suspended tariffs on lentils from Australia, amongst other countries, until September 2022 as a means of managing food inflation for domestic consumers. 248 However any supply response by Australian farmers has been hindered given the short term nature of some of these tariff policy shifts. 247

Outlook

Stronger Primary Industries Strategy

Horizon scanning for food safety threats using artificial intelligence

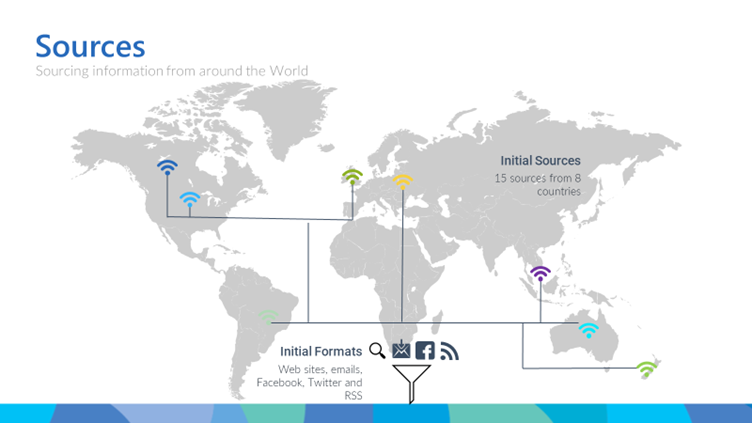

International Food supply chains are complex, with products and ingredients widely distributed across the globe. Contamination events during production or manufacture may not be communicated to international trading partners in a timely manner, with most alerts occurring in the source country prior to notifications further down the distribution chain. In recent years, outbreaks of foodborne illness have occurred in Australia weeks or months after the same or similar products were recalled overseas. Proactively scanning for potential incoming food safety threats is an important task, but is time and physically resource intensive due to the number of alerts generated from various source countries.

Strategic Outcome

In the example shown below, the AI horizon scanning tool is able to search an international food safety bulletin and extract the key words related to a product recall of protein bars in the USA that have been contaminated with E. coli. This information can generate an alert to authorities in Australia in real time for review of the same or similar products that have recently been exported.

With sufficient data built up over time, the horizon scanning tool will be able to detect ‘spikes’ in a particular hazard or food that may be above expected background levels. These alerts can be a trigger for additional investigation of potential threats outside of a specific product coming into Australia.

Additional functionality is expected to be built into the AI tool in coming years, including the ability to scan local sources of information in NSW and Australia to look for food safety threats in domestically produced goods.